Imagining Theatres with Daniel Sack

September 29, 2017

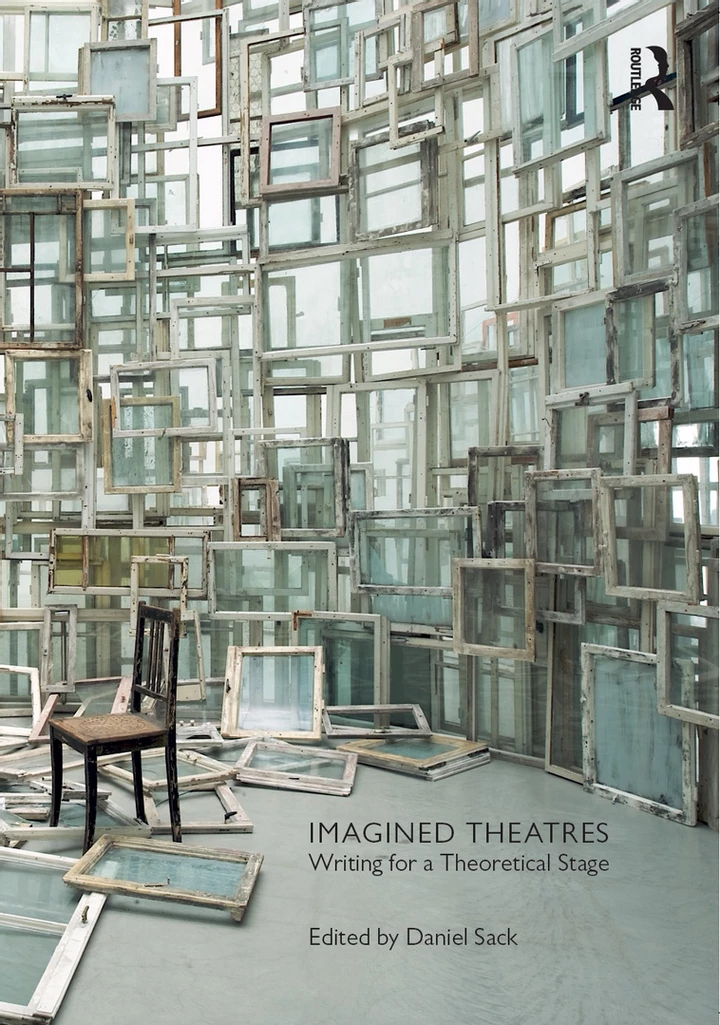

Recently American scholar, critic, and theatre-maker Daniel Sack edited the book Imagined Theatres: Writing for a Theoretical Stage

(Routledge 2017), which brings together a curated selection of visions for the theatre and the world by contemporary artists, scholars, curators. These contributions—each no longer than a page—describe imaginary performances that stage what might be possible and impossible in the theatre. Daniel holds a joint appointment as an associate professor in the Commonwealth Honors College and the English Department at UMass Amherst. His research and writing focuses on modern and contemporary theatre and interdisciplinary performance, performance theory and dramatic theory, and critical writing as a creative practice. Fusebox curator Anna Gallagher-Ross caught up with Daniel over Skype while he was in Edinburgh attending the Edinburgh Fringe Festival and they discussed the origins of the book project, the future of Imagined Theatres online, and what imagination can do for us in our current moment. You can browse through a selection of Imagined Theatres here.

Anna Gallagher-Ross: How did Imagined Theatres come about?

Daniel Sack: I suppose the inspiration came in graduate school when I was working toward a doctorate in theatre history and criticism. I occasionally did some directing, but often when I didn’t have the time or the means or the skill to stage an idea, I’d turn to the page, asking myself: what would I do if I could do anything? What are the limits of what a performance can be or can do? What kinds of questions can we ask of the theatre? What kinds of answers might it provide? I started writing down different ideas for performances that I might not ever stage. This writing became a regular practice for me, a way to make a problem concrete, often without resolving its troubling strangeness. It also helped me think through my continued love for the theatre in all its awkward and frustrating ways. It helped me think about why I kept returning to this antiquarian art form? I felt such anticipation and expectation when I arrived at the theatre: What was I hoping to find at the other side of that nightly dimming of the light?

Many of the artists and thinkers of the stage I know talk of their imagined projects—things they’ve always dreamt of making happen—conceptual approaches to a favorite play, proclamations outlining what they wanted from the theatre even though it often left them disappointed. So many of us write or tell stories for an interior stage that resides in each of us. I began sharing my own versions of these imagined theatres, with friends and then tentatively out loud in lectures and on the page in printed journals. And I began hearing other people’s imagined theatres. While I was writing about my own horizons of what was possible, others showed me horizons far beyond my sight. This was more exciting than anything I alone could imagine. So I thought all these imagined theatres should be compiled into a book a person could read and engage with.

AGR: How did you go about selecting the artists, scholars, curators we find in this book?

DS: It started as a series of invitations to people who I knew were already working in this manner; people like Tim Etchells, artistic director of Forced Entertainment, a collective based in Sheffield, England, who has for a long time been creating pieces that collect fragments of stories that might be, whether in the theatre or in the world-at-large. Etchells sees theatre as a kind of machine that is constantly producing new fictions, new realities out of the scattered pieces of other stories. Or the Italian director Romeo Castellucci, whose stage work gives shape to seemingly impossible ideas and images and whose working notebooks contain otherworldly descriptions of events that he might stage someday. Also the work of director Lin Hixson and dramaturge Matthew Goulish, of the Chicago-based performance companies Goat Island and Every house has a door, who play with ideas of possibility and impossibility in concrete terms through elegant but simple physical actions; or performance theorists like Peggy Phelan and Rebecca Schneider who are thinking about writing as something that is doing something as well as describing it, performing on the page. These were some of the people I first approached—those whom I admired and who had already reconfigured my sense of the what theatre was or could be—but I wanted to move beyond my own idiosyncratic story, and so I started asking colleagues and other contributors for suggestions. I wanted to include different aesthetics, different perspectives, different ways of working, different forms of theatre. I was trying—in what I knew was a futile way—to capture some comprehensive vision of what the theatre is. And eventually I had nearly one hundred people involved in the project. There were so many more I could have included, that I wanted to include, but there is only so much a book can hold, so I decided to limit it to contributions from the US, Canada, Ireland, and the UK.

AGR: If you open the book you see the left side of the page presents the imagined theatre and the right hand side presents a “gloss” or theoretical response by the same person or another artist, scholar, or curator. Could you talk about the format the book takes and also how you decided to pair these contributions/contributors?

DS: I thought that a single page would be a challenging limit for the imagination, but I also wanted to keep with the idea of each page being a stage, within a kind of two-dimensional proscenium frame. I was also thinking of the experience of moment-to-moment reading, of each turn of the page revealing a new theatre. And as a scholar who is also very invested in creative work, I wanted to see these typically divided forms—theory and practice—bleed into each other. We often see criticism and creative work as antagonists, as not speaking the same language; I wanted to break that distinction down and show how the great artists of the theatre are also the great thinkers of the theatre. I also wanted to show that scholars, too, are artists in their own right, thinking and revising what we think the theatre might be. So I split the book in half: on one side theatres, on the other side a piece of theory, or what I call a “gloss,” that responds to each imagined theatre. Of course, the difference between the two is intentionally slippery—some of the glosses sound more like “creative writing” than the imagined theatre they are responding to. The conversations and collisions that occurred between these texts were sometimes between collaborators who had worked together for years, and others between people who had never met before, maybe two artists reflecting on each other, or an artist reflecting on a theorist, and vice-versa, all leading to serendipitous discoveries.

AGR: Another exciting thing about this book is the way it foregrounds the role of the reader: there is a sense of liveness, that by reading these texts, the reader plays a role in completing or producing the theatrical event….

DS: Yeah, that’s right! In encountering these texts we become the actor, designer, director, and stage manager. Reading is a kind of private theatrical event that we project onto our interior stages, spectating through the mind’s eye. We cast the characters, we color the sets, we feel the pain or the joy of whatever we are reading. So there’s a kind of one-to-one relationship between the page and the reader—this incredible private experience—but what I am also hoping happens in encountering this book is the awareness of the communal nature of the art form, created through a multiplicity of voices and perspectives. When I am reading these texts I know that whatever I’m imagining inside them is not the same as what was originally imagined or what you might imagine when you read the same writing. It happens differently for everyone. I hope the book is an invitation to meet another imagination half way.

AGR: Each contribution demands something different of the reader. Could you speak a bit about the interesting forms these contributions take?

DS: There are scripts, of course, some with characters from any living room drama, but others naming planets or black holes as protagonists. Some take the form of poems, sets of instructions, or manifestoes like Ju Yon Kim’s proposal for a public theatre that would be like jury duty or Jen Harvie’s simple directives for a show where older women appear onstage doing what they would like to do. For some the visual nature of the printed word is very central, like Ant Hampton’s response to Claire McDonald’s imagined theatre, where he takes her text and blacks out much of the page, leaving only intermittent words that together form a new text, or Nature Theatre of Oklahoma’s decision to produce a microscopic text only legible through a magnifying glass, but also some, like the gloss by Rajni Shah that ends the volume. were written to be read out loud—they are about voice, about breath—and so they come even more alive when encountered like that.

AGR: The next step for this project will be an Imagined Theatres website. What’s your plan for this digital stage?

DS: This fall we will be launching an online journal which will publish issues every 3-4 months. The first issues we’re looking at focus on geographic areas the book couldn’t cover: a first issue focuses on South Africa and the following one on Australia. After that, we’ll have an annual open call to include writing submitted by readers. Eventually we hope move into translation work, as well as develop thematic issues, such as inviting architects or set designers to draw and create a visual representation of their imagined theatres. So we are ultimately moving away from the beginning confines of the page and the book, heading toward a more multi-media model made possible by the online platform. We’ve lined up editors from different regions for each of these issues so that I’m not the authority or the force guiding this. My hope is that this will be something that other people take on and take in different directions.

AGR: It’s so timely reading a book like this here in Austin. With the loss of incredible venues such as Salvage Vanguard and the Off Center and rising rents, it has become extremely challenging for our community to make and present work. This leads me ask you: why this project of imagination now? Imagination of all kinds feels important in this precarious moment we are living in in the United States, politically, economically, artistically. What can imagination do for us right now?

DS: I hope that we can use the theatre as a space to imagine other spaces, other worlds, other ways things could be or should be. That’s a really utopian opportunity that the theatre offers us. I think all the arts do this in different ways but there is something about that inherent live, communal encounter that the theatre relies upon—the human to human connection. So it’s about tapping into that but also seeing limitation as a place of possibility or opportunity rather than something stifling. A lot of the imagined theatres in this book tell us what we want of the future and how the theatre might get us to that place. Other imagined theatres are dark and terrifying and threatening in order to show us what’s happening right now that we’re unaware of, or unable to see, or what might happen with just a slight twist on the logic of the everyday. And then there are texts that are resolutely banal in their re-imagining of the everyday—what should be happening, but isn’t: fair representation, fair pay, or accessibility. These pieces show us what it might look like to have a theatre that really did take its ethical responsibility seriously or a theatre that presents a model of the larger world. They become a wedge in the cracks in society, placed to split them open or to seal them up. Imagination also aims to provide people, whether scholars, readers, audience members, artists, whoever, the opportunity to stage events that they might not be able to stage right now. In considering loss of space, diminishing resources, political censorship or pressure—all the issues of access the arts face with alarming regularity—this project and these conversations, might be one of many hopeful venues where work can still be happening, even if we don’t have a theatre season or a stage to realize the theatre that we want to realize. In this precarious moment, these imagined theatres feel like momentary places of stability, safe experiments in destruction, manifestos or memorials for what should be done, what will be done.

CLICK HERE TO BROWSE THROUGH A SELECTION OF IMAGINED THEATRES