For the Love of Plastic OR How Two Archaeologists and an Artist Bonded Over What the Wor

December 1, 2017

Artists are no strangers to university and college campuses. Some of our nation’s most renowned academic institutions often play host to some of the world’s best artists and their works. University presenters now often operate in the same circuits as professional arts organizations without campus affiliation—it is not strange, for example, for a show to have its world premiere at Carolina Performing Arts (CPA) at UNC Chapel-Hill and then travel straight to the Brooklyn Academy of Music.

Far rarer, however, are substantial, long-term engagements between visiting artists and university faculty. Eager to foment deeper connections between the arts and academy, CPA, under the leadership of Executive Director Emil Kang, earned an Andrew W. Grant Mellon grant to support collaborative research between artists and UNC faculty. Officially launched in fall 2017, the DisTIL (Discovery Through Iterative Learning) Fellowship brings artists (four total) to UNC over one or two years to work with faculty in departments outside the artists’ own area of expertise. The length of the fellowships allows collaborators to build projects as well as a necessary trust, respect, and shared vocabulary. DisTIL’s intended outcome is artistic-academic collaboration with bi-directional effect: the faculty members bring their research, teaching, and specialized knowledge to enrich the artist’s work, while the artist brings her creative processes and insights to enrich their scholarship. At the end of each residency—and possibly throughout—artists publicly share their works-in-progress with the UNC and local communities.

Artist, puppet designer, and director Robin Frohardt is one of two current DisTIL Fellows (the other is musician, composer, and activist Toshi Reagon). Robin came to the fellowship with a major project already on the horizon: a large-scale installation called The Plastic Bag Store, which will open in CPA’s new off-campus space CURRENT ArtSpace+Studio in fall 2018. The Plastic Bag Store emerges from Robin’s fascination with our thoughtless, almost comical overuse of plastic and its long-ranging effects on our environment due to its non-biodegradability. Robin will construct a fake grocery store in a real storefront (CURRENT will occupy a new building in Chapel Hill’s commercial downtown), one whose food products are made solely of plastic bags. The store will also feature an interactive puppet play about future archaeologists who unearth and try to interpret the plastic detritus that will remain on the planet long after we are gone.

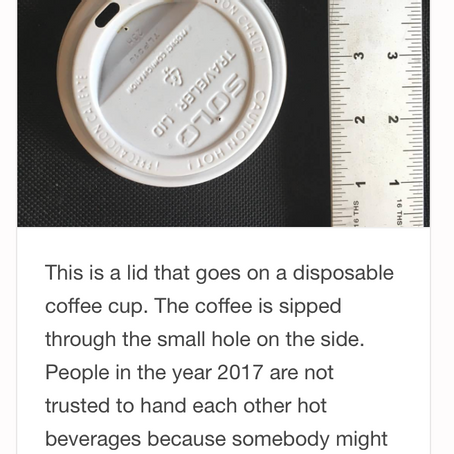

Appropriately, two of Robin’s faculty collaborators, Anna Agbe-Davies and Eric Deetz, are archaeologists. The two scholars, who happen to be married, both belong to UNC’s Anthropology department. Through their collaboration, the trio has created an Instagram and accompanying Tumblr called Plastic Archaeology that catalog and describe all the plastic objects around us today. The professors have also involved their students in this exploit: to date, about 400 posts come from their undergraduates. In addition to more intangible influence that the project and accompanying discussions will certainly have on The Plastic Bag Store, the “exhibits” created digitally through the Instagram interface will become a physical part of the final piece.

As the postdoctoral fellow overseeing the DisTIL program, I asked Robin, Anna, and Eric to speak with me about their collaboration and how it has changed their ways of working in their respective fields.

—Alexandra Ripp

AR: For starters, it would be great for each of you to talk about your own work—what you have done before this collaboration or continue do alongside of it.

Robin Frohardt: I am a visual artist and a theater artist, and I make puppets and installations and short films and animations. I tend to use recognizable materials to create elaborate worlds. I love cardboard and plastic bags—things that we usually think of as mundane and banal. I like to use them as a storytelling device and to create magical environments.

Anna Agbe-Davies: I’m a professor of anthropology at UNC-Chapel Hill and also an archaeologist. I like to think of my work as focusing on the modern period, but extending in two directions. I am thinking about the present moment through the lens of archaeology, using archaeological techniques to try to understand ourselves a little bit better, but I’m also pushing back the understanding of where the “modern” starts—not just to the beginning of the 20th century, but back to the age of exploration. The kinds of transformations that occurred in that moment have had real repercussions for how we’re living right now.

Eric Deetz: I am also an archaeologist and I lecture here at UNC-Chapel Hill. My area of focus has been on early colonial sites, from the 1500s into the 1600s. I also got into working in cultural resource management, which is doing archaeology for when you need to build a highway or a shopping mall. You go out and dig whatever’s there, and through that I was sort of forced into looking at 20th century material and more modern stuff than I normally would have. It has become pretty clear all of a sudden that the 20th century has become valid for archaeological research and something that we have to consider in our work.

AR: So, I’m curious—Robin, you didn’t mention any experience with archaeology or anthropology, and neither Anna nor Eric mentioned the arts. Robin, have you ever thought of working with anthropologists and Anna or Eric, have you ever thought about working with artists?

RF: It hadn’t occurred to me until this fellowship and I think that’s one of the exciting opportunities provided by DisTIL. I was really interested in thinking about plastic in our lives. Humor is really important to my work and, as I mentioned earlier, so is the banality of daily life. I’m interested in highlighting the ridiculousness of all the practices and objects in our lives and all the things we overlook. I started to think about those objects and the discrepancy between how little time we spend interacting with them and how much time they actually exist. I thought, “Oh, this thing that I think is completely meaningless is actually this connection to people in the distant future. Not the things I think are super important or everlasting, but instead this thing I stir my coffee with is the thread that’s tying us together.” That idea led me to talk to people at UNC who think like that, people in the fields of archaeology and history, who study things that other people maybe thought were insignificant in their time but are extremely significant.

AAD: I think the connection that I would’ve identified before this collaboration has to do with the kinds of output that archaeologists and artists often have. I spent a lot of time working in a history museum, so I think about the ways that we display things as a means of communicating with people and about the ways people encounter objects. When Robin started talking about her idea of modern plastic objects in an archaeological museum, that connected in my mind with the kinds of ways that we try to tell stories with objects. We do so with a different sort of creativity than an artist uses, but I see a lot of overlap in how we try to convey what we have to say.

ED: I’ve always thought about the arts. In my former life, I was an art school dropout, so I have a background in printmaking. I also did a lot of scenic art for theater for a while. I’ve often looked to literature, which has been something that I don’t think archaeologists have paid enough attention to because it’s often fictional. But fiction is made up of real things: William Faulkner talks about things that were actually going on in the South. Archaeologists have looked at genre paintings from the 17th century to help identify material culture—it helps us identify social context or date objects. So, why wait hundreds of years to bridge that gap between studying the arts and studying what people are doing?

There’s also this archaeology lab in the City of Alexandria in Northern Virginia—it’s in an artist’s studio! The archaeologists who founded it really felt strongly that archaeology should be considered as an art rather than a science, even though we use a lot of science. A lot of people bristle at considering archaeology in terms of art, but there’s so much cross-over.

AR: Can you all talk about the project you’re all working on? How did it come into being?

ED: One of my biggest preoccupations is that everyone thinks that archaeology is just about obsessing about the past. But really, it’s not. I mean, we study the past, but so much of our time is spent worrying about the future— how is our work going to be perceived, why are we doing it. Our work is for the future. And then, you start extending that idea out and ask the question: what do archaeologists in the future need? That’s really one of the topics we overlapped with Robin on: the future of plastic, and how it’d be looked at from an archaeological standpoint. It was a really natural connection.

Anna and I had been collaborating on a couple of projects that focused on the twentieth century, and we found we were a little bit in the woods with identifying some of the objects. We can identify objects from the middle of the 1700s very easily; there’s a lot of scholarship. But because of the post-industrial age, and just the massive amount [of materials] and ephemera, this data just gets lost. We thought that it would be great to document that. It was a project we’d already been thinking about, and I was facing the idea of getting an expensive website and a web designer. Then, with this collaboration with Robin, we realized, “We could just do this together.” And it’s really taking off. It’s a list of everyday plastic stuff, all these bits and pieces. It’s a way to document the state of things.

AAD: I’ve been interested for some time in the ways that the Internet and social media allow ideas to move and provide broader access to information. Specifically, I’ve been learning about techniques for crowd-sourcing participation in archaeological studies. Not everyone can visit a site, or go to a lab to volunteer, but lots of people can engage via technologies that they already have access to. I was thinking about broad access and high volume participation. Eric was the one who I think understood that because archaeologists think about material culture differently from the general public, we actually needed that perspective to get at what plastic means today. Along the way, it is going to build an archive that we can use to better understand how to approach the plastic that we find doing “traditional” archaeology—that is in excavations. Sites only need to be 50 years old to be on the National Register, and archaeology is one means of deciding if a site is eligible. But if we don’t have the methods and resources to analyze and understand a significant proportion of the artifacts we find, that process is somewhat compromised.

AR: Robin, could you talk about making the Instagram account and curating it? How has that process been?

RF: Well, it was surprisingly easy. When we first started it, I thought, “Next we’re going to need a fancy web developer that’s going to make a website that looks like our Instagram feed and is searchable with these hashtags.” Then I ran it by a millennial, and they suggested Tumblr, so I was able to make the website basically for free along with the Instagram account. The Tumblr has the same posts as the Instagram account, but because it’s a website, we can add tabs for materials on teaching with the archive, research or input from other disciplines about plastic, information about us as individuals.This platform is also accessible to people who don’t necessarily use Instagram.

The challenge is keeping regular posts—I can get overwhelmed with other projects, but it’s also so fun when I realize I haven’t posted in a while, and then I can see that you guys have posted stuff. It makes me think, “Oh, this is great. This is an actual collaboration.” We’re actually both doing it.

ED: One of the great things about having Robin take the lead on the Instagram is that, as archaeologists, we would be a little drier. We’d say, “This is what it was, and this is where it was made. Full stop.” But Robin’s posts are really interesting and humorous. She brings in context for the object that we, who just explain where was it made and how old is it, wouldn’t address. If people take that approach as a model, we would learn and document so much more about the social value and context of these objects. If we branch out like this—particularly when people comment on these posts—we’ll get a body of information. We’d give our eye teeth for that kind of information on the 200-year-old objects that we’ve dug up.

RF: I wonder if people in the future will get our humor! Probably not. For me, the humor is just in stating the obvious. [Holds up a small piece of plastic] This was something I was going to post later today—it’s a fun little hook thing that just hangs one pair of socks. Even just saying what it is and what it does makes you think, “Wow. That’s dumb.”

AR: The hashtags on the Instagram are so ingenious because they actually provide a categorization tool for you, right?

AAD: Yes. The hashtags also put these objects out in other domains. So, if somebody who is not thinking about plastic or archaeology at all uses that same hashtag, then they might come back to the account and get looped in. The network capacity of Instagram is really fascinating to me. I’m really excited about the collaboration possible with the Instagram account and getting not only our perspective on plastic and how it relates to archaeological understanding, but sort of crowdsourcing information about it. I’ve become very interested in how knowledge is produced, not just by a single individual, but by collectivities of people. To have this low-stakes, instant gratification participation is really broadening our ability to understand the material that we have in front of us. To, in a sense, democratize that process, to make it less ivory tower, isolated, and specialist-dominated is stimulating for me, coming from my own specialist framework. It’s also enriching for me as a human to see what other people are thinking and how they’re interacting with the stuff around them.

AR: Robin, you’re coming back for a few more visits this year. What do you three think are the next stages of the collaboration?

RF: It would be nice to talk more about what we want to do with the website, and I’m interested in seeing how students engage with it. It may end up being a tool that’s useful in classroom discussion, and it could be shared with the broader academic community, too, to get more people to contribute to it—either by assigning to students or just talking about it. We can definitely refine and expand upon what it means and how it works. What’s there now is a rough draft. I’d like to talk about how to expand its visibility online, too.

AAD: One of the things that’s really interesting to me is something Eric had mentioned: that somebody we knew that didn’t know that we were part of the project had found it via somebody else, so we know it’s out there in circulation.

ED: There’s a woman I’m friends with on Facebook, a former student and a friend of Anna’s, who posted the link to Plastic Archaeology and said, “This is my new obsession.” She had heard about it somehow, and somebody commented on the post “You’re welcome. I thought you would like this.” I didn’t even know who that other person was, so that was neat to see. I think this thing’s got legs—it could go somewhere.

RF: Yeah, my friends are pretty into it. It’s hard to know who’s following and who’s not, but I was at an art opening for my boyfriend last week, and someone came up to me and said, “Oh, thank God you’re here! I found this, and I thought you might want it.” And they handed me this weird piece of plastic.

ED: [laughs] Nobody wants it, that’s the point!We’d talked with Robin about doing something like PlastiCon or Plastic Day, and then we were talking to archaeologists who were working in the contemporary period, one of who had just won a McArthur “Genius” Grant. There are people outside of UNC who might come and be able to address the modern-modern-modern period, like now.

AR: You could even have your own conference. It sounds like it’s a whole field-wide interest.

ED: Strangely, they’re a little more ahead of things in Europe. European archaeologists have a stronger history working with artists, of collaborating with either film or even visual art to create an exhibit for all the sense that overlaps.

AR: I was going to ask about interdisciplinary work for your perspective, especially with artists. What do you foresee as challenges? Why don’t people do it more? Why is it that European archaeologists are doing it more than we are?

ED: I think that there’s always been this idea that the American archaeologists are more theory-driven and maybe that takes them away from the reality and materiality of stuff.

I don’t know that there are any challenges for our project. We could’ve gone a long time and never done this, but we were introduced to Robin and realized there was an overlap in aspects of our work. Quite honestly, for Carolina Performing Arts to create these opportunities is wonderful—otherwise we’d just stay in our offices and our labs forever and not reach out to anybody.

AAD: I think silos— intellectual and disciplinary—are an important factor in why interdisciplinary work is rarer, though I don’t know if that speaks to the difference between the U.S. and other places. There are plenty of artists who play around with the idea of archaeology and will dabble with the concept of making art out of archaeological perspectives on material culture, but it doesn’t always speak to the archaeological mindset. The way that Robin approaches it—I can’t really put my finger on what was different about her stuff. It has to do with what you said at the outset of this interview, Robin, about your interest in the mundane and in ideas of what this material culture meant. For you, it isn’t about the superficial qualities of what makes archaeology archaeology, like the form of archaeological exhibits. It’s about the ideas and orientation that make archaeology archaeology, and that really spoke to me in the work of yours that I first saw.

AR: Robin, have you ever thought about working with academics before this fellowship? Has that been something that has interested you?

RF: No, this has been a first. I exist in my own silo, too, so it’s cool to engage in a new way. The Plastic Bag Store is definitely my largest project to date and addresses a much larger issue than anything else that I’ve made before. Also, I am more interested now in making art than theater, because I feel like art has to be real, in my opinion, and theater is fake. I love faking things, and I’m always going to put on performances and shows, there will always be a narrative aspect to my work, but, for instance, if you were building a set for a theater and you wanted to have a thousand paintings on the wall as part of it, you would fake it that they were all different. You would photocopy them or Photoshop them. You’re just creating a scene, but if you were making a piece of art that is a thousand paintings, they each need to really be real and actually different—they need to be the thing. I feel like in art, you can’t just say you did something— you have to actually do it. I’m interested in doing things that actually exist in the world and aren’t just cool stories on stage.

That’s why this project appeals to me. It’s a real storefront and beyond that, having this other aspect, that it’s engaging the real world and all of the real crap that we deal with. It’s not like I’m just finding pictures online of plastic. I’m not creating a fake website that looks like an archaeological website. I’m trying to actually do it, actually document it. That really appeals to me, so I think from now on I will always seek help from academics, because the work needs to be real. It needs to have real research behind it, not just be a scene that I’m painting.

AR: Is there anything else you want to add about the work you’re doing or about interdisciplinary collaboration that you feel is useful to other people working in the same way?

ED: Sometimes, if you’re so focused on a particular thing, if you’re really studying intently or doing a lot of research, if you make time to read a novel that has no connection to what you’re doing, it blows the dust out. It opens up the channels. To be able to stretch beyond what our normal routine is and still be productive and fruitful. It has that same sort of “clearing out the fog” effect. I think most archaeologists think in creative ways, but we’re not always given the opportunity to engage that creativity. This collaboration really highlights the shared real estate between the two fields.

AAD: To your point of doing something completely different outside of one’s comfort zone, when we were talking about the Instagram, it started to feel to me like it was running away from us, like it was getting really fast and I wasn’t in control. I didn’t know what it was going to look like in the end, and it didn’t look like anything else I’d ever done before, so I was really uncomfortable. But that’s the moment, where you’re kind of off balance, that you can really make a major transition. You can make a major shift in your thinking if you don’t know what’s going to happen next and if you haven’t worked it all out ahead of time. This project is allowing me to nurture the creative complement to the analytical side that I spend a lot of time in. It’s been really stimulating for me.

ED: As we said in the beginning, archaeologists are almost in a crisis, not knowing what to do with all this plastic that we’re finding on these modern sites. Now, this project isn’t necessarily showing us how to treat this material, but it gives us the excitement and the fresher perspective we need to turn back on the collections that we’re developing archaeologically. It’s going to be a way to keep the enthusiasm, instead of throwing your hands up and saying, “What do we do with all of this stuff?”

AAD: It’s entirely possible that the models that we’ve developed for other kinds of material culture are going to be inadequate. Take the hashtags—based on the prior model, we would say, “how do these hashtags help us make sense of these things if they don’t tell us what they’re made of?” The chemical composition or the manner of shaping is so fundamental to our understanding of what something really is from 300 years ago. But why does that matter? Why do I feel like that’s something we need to hashtag about every single one of these objects? It’s making me think that maybe this will look nothing like a catalog that I would’ve made for ceramic objects or stone tools. And it’s only through engaging in this process with an open mind that I’m maybe going to be able to figure it out.

AR: That’s interesting. That through this project, you might realize that the model that you’re used to using is obsolete.

ED: My question is: will this process lead to better insights into looking at older material that’s not plastic? It offers a new way of categorizing things. I’m not sure we’re going to have the attached information for older objects, like we can get from the plastic posts. What struck me about the Instagram was all that information that was going to be included with all these objects. We don’t have that on older materials. Nobody’s sitting around in Staffordshire, England in 1750 with everyday objects, saying, “Whoa, this is really interesting.” And yet that’s so relevant to the stuff we’re looking at now. I don’t know if it would work to use this process for older objects, but it does shake things up a bit.

AR: Robin, how does Plastic Archaeology relate to the The Plastic Bag Store installation?

RF: I’m saving all the things that I’ve cataloged, but I keep accidentally throwing that stuff away. [laughs] Part of the installation is in a future history museum. The writing in my original vision will now be different because it was originally about total misinterpretations of objects as opposed to literal interpretations. Anna and Eric, when I visited your offices, I took pictures of the charts and displays in the hallway that show pottery and other specific things from different eras. I think it would be cool to develop some displays or documents like that for The Plastic Bag Store. Maybe we could make some about the Plastic Archaeology exhibit that really do identify things and use some of the same academic language. I do need to create a whole museum for the show, so it seems a waste not to include our work in some way. I’m not sure yet beyond that, but this is so interesting and so cool, and I love looking at all of it together, seeing the grid of everything on the website. I really do like the way the things look all together.

Photo Credits:

All from the @plastic_archaeology Instagram account by Robin Frohardt, Anna Agbe-Davies, and Eric Deetz as part of their research for The Plastic Bag Store.