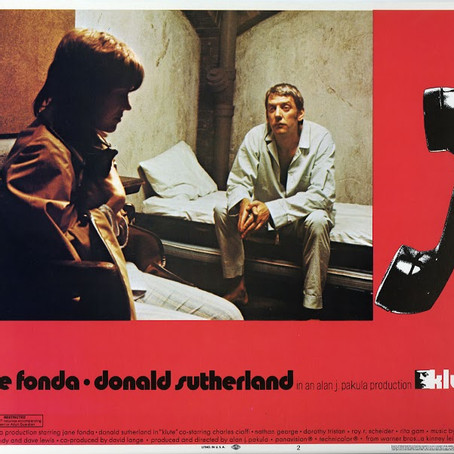

Nice Work—Acting in Klute (1971)

December 20, 2017

Scene one: A line of young women in chairs. They’re sitting under three enormous images of a model’s face in close-up, adorned with

jewels. A man and a woman walk past the women and summarily dismiss each one. Bree is rejected with barely a look. She has “funny hands.”

Scene two: Bree shows up at a nondescript apartment. A man opens the door. She handily controls their exchange, purring that she finds what he wants to do with her “so exciting,” but “it’s going to cost a little more.” He pays her immediately. She checks her watch when he isn’t looking.

Scene three: Bree as Saint Joan. Irish accent. Unbearable earnestness. A man walks in the foreground of the image, blurry, interrupting, and waves his hands as if directing her. Then he turns away to face someone off camera, and shrugs: not impressed. “Thank you!” a voice calls out, “Very interesting accent.”

Scene four: Bree as a movie goddess. A runway down a long hallway into a moody backroom. She enters in a ball gown, fur around her neck. The music swells. She’s on her way to see a client, an old man who never touches her, just pays her to deliver a monologue in character as a star.

Bree Daniels has two performance careers. In one she gets the part every time. In the other, she never does. One is supposed to be exploitative, dehumanizing; the other actually is. Bree tells her therapist that she wants to give up prostitution and focus on her acting. But why, when the labor conditions of the former are so much better? When Bree goes on calls, she always has an appreciative audience. She “knows she’s good.” And it’s good work. When she was doing it full time, she could afford a penthouse. Now she’s in a dingy studio. She pounds the pavement, shows up at open calls, acts her heart out in basement theaters, and nobody gives a shit.

Klute, Alan Pakula’s morose thriller from 1971, gives the old analogy between actress and prostitute a post-’60s twist. The film is ambivalent about its own argument: that acting is more sexist than sex work, less empowering than prostitution, and a worse job all around. As a call girl, she’s in demand; as an actress, she’s utterly dispensable. Ironically, however, the surplus labor force that makes Bree expendable as an actress is also what allows the film to assert that acting is something other than exploitation. After all, if Bree wants to act despite its terrible labor conditions there must be something about acting that gives it value outside of commerce. Call it art –– and look for it in Jane Fonda’s own aggressively crafted performance as Bree. The fictional world of Klute may not want Bree to act, but we in the film’s audience know how to value Jane Fonda’s acting, how to read its quality, how to see it as “good.” Klute compensates for its cynicism about acting by holding its own performers outside the exploitative economy it represents.

Nowhere is this maneuver, and the cost of achieving it, more visible than in the film’s climactic scene. Bree is in her client’s office, the one who pays her to act like a movie star, but he’s not there. The man we now know is the film’s killer shows up instead, and in the course of revealing his crimes, forces Bree to listen to an audio recording of his murder of another prostitute. We hear a menacing dialogue, and then the woman scream. As we listen, we’re watching Bree, who is crying. It’s a bravura moment, as crying scenes often are, but a strange one. Fonda looks down and away from the camera lens. Half her face in in shadow, and we only see the tears coming out of one eye until they well up on both sides of her nose, which, shockingly, starts to drip. The performance is so impressive that its obscurity might go unnoticed. Why is Bree crying?

It’s not panicked crying, as the circumstances of the scene might call for. In fact, it’s hard to find any narrative justification for Bree’s crying at all. It only truly makes sense outside of the fiction: Bree is crying because Jane Fonda is a good actress. And crying is a particular kind of acting’s trump card, both a sign of virtuosity and a shorthand for authenticity, both a high-level professional skill and something other than expertise. Fonda, at the time a devoted student of Lee Strasberg at the Actors Studio in New York, was versed in the ideology of acting that he fashioned through an uneasy combination of technical skill and emotional exposure, which required some gymnastics around the idea of “work.” Strasberg’s method of acting was supposed to be a professional practice: the whole point of “the method” was to make acting a craft, a set of repeatable and practicable techniques. That professionalism compromises the aesthetic ideology that locates art outside of the workaday world, and thus calls into question the special status of acting as an art, the kind of calling that one might give up more rewarding employment to pursue. This special status is what method acting buys back through the excavation of inner demons and psychological wounds. The demand for emotional nakedness closes the circle: thus the endless accusations that Strasberg’s techniques amounted to a kind of psychological peep show, with actors forced to expose their private traumas.

In the climax of Klute, the refusal of the film’s own medium (we’re watching a woman not watching) enables an important substitution: we’re not watching a snuff film, we’re watching art. Nicholas Ridout, describing the critique of aesthetic ideology that separates art from the material world found in the writing of Romantic-era dramatist Heinrich Kleist, shows that it depends on a refusal of the theatrical encounter, with its visible labor relations and troubling nearness to erotic exploitation. In Ridout’s reading, Kleist’s theory of an actorless theater (in “On the Marionette Theater”) stages an attempt to rid theater of “the unease of face-to-face encounters” that lay bare the erotic-economic relation between ourselves and the actors we’re watching, a relation too similar to that of prostitute and client. [1]

Jane Fonda’s tears, glimpsed in shadow, her eyes lowered, her face in three-quarter view, marks its distance both from the line of women with which the film began and from the glamorous movie goddess Bree already played in that room. But of course, watching a movie star’s nose run is its own kind of prurient pleasure. It’s an exposure more titillating than any physical disrobing would be. And the content of the scene offers a disturbing commentary on the role of the aesthetic alibi in mediating between the woman as erotic object and the male sadistic subject. The prostitute is dead; long live the actress.

Shonni Enelow is the author of Method Acting and Its Discontents: On American Psycho-drama (Northwestern University Press, 2015), for which she won the 2015-2016 George Jean Nathan Award for Dramatic Criticism. She is an assistant professor in the English department at Fordham University.

________________[1] Nicholas Ridout, Stage Fright, Animals, and Other Theatrical Problems (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press), 27–28.