Joseph Keckler on Making Work and the Tricky Dance of Self-Articulation as an Artist

January 5, 2018

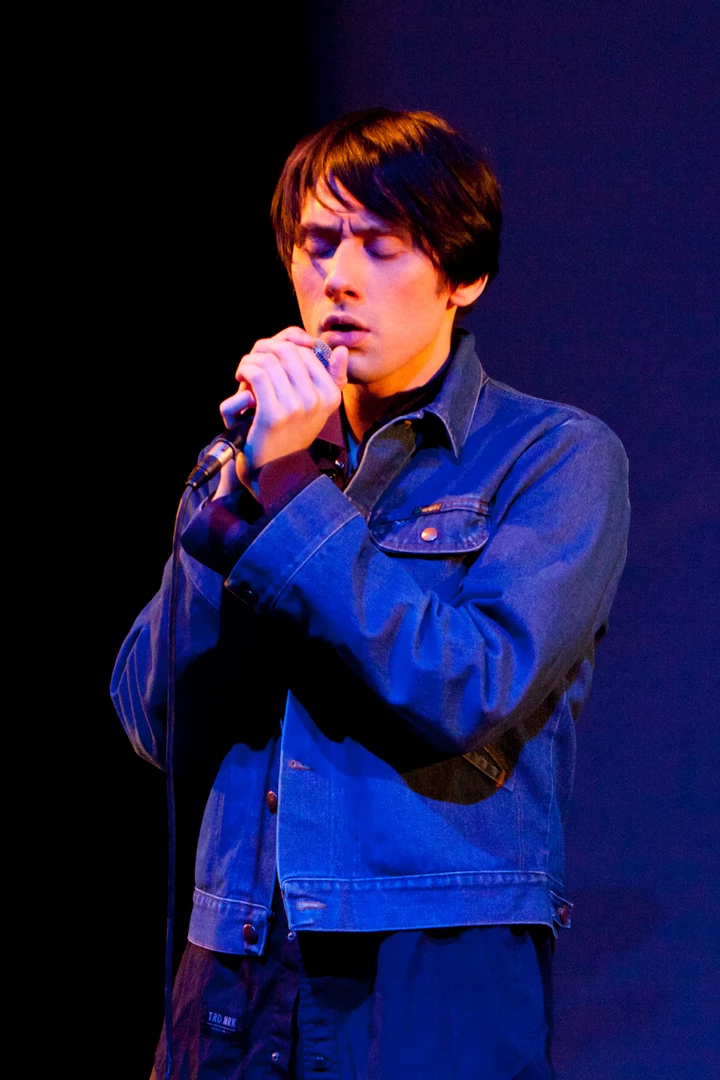

Joseph Keckler is a vocalist, writer, songwriter, and performance artist based in New York City. He creates miniature operas about contemporary life, haunted torch songs, and narratives that combine humor, autobiography, and classical themes. Joseph has received a Creative Capital, NYFA Fellowship, Franklin Furnace grant, and Village Voice Award for “Best Downtown Performance Artist.” He recently published a collection of writing called Dragon at the Edge of a Flat World (Turtle Point Press in 2017) and is currently finishing an album of music. Joseph charmed the audience at the 2017 Fusebox Festival Hub and will return to Austin to perform at the Rollins Studio Theatre on January 23nd and 24rd, 2018, as part of a new partnership between Fusebox and the Long Center. Fusebox curators Betelhem Makonnen and Anna Gallagher-Ross talked to Joseph about what goes on in his mind when he makes work, the tricky dance of self-articulation as an artist, and his relationship to opera.

Betelhem Makonnen: Could you tell us how you approach the beginning of a work. Does it come out of darkness, or is it already in the light and you work towards it?

Joseph Keckler: Maybe it stays in the darkness and the audience has to follow me in, stumbling, to grope around after it. No, it does come out somehow. Even when I devise a project that is conceptually-driven, I go through a process of—it hurts to say it, but— “discovery.” And when I write any story or song I have a person, character, image, scenario, or episode from my own life or a particular constellation of images and events in mind and then I develop it.

I write “arias” that involve humor, foreign languages, and are written in a more conscious way. However, I also write non-comic songs in English which are more abstract and image-based, with more elusive narratives. I might use a cut-up process for these, sometimes drawing on found text or classical texts. I usually write these best if I’m in a trance state. There’s a duality: on one hand, the funny material often depicts a personal experience of being out-of-control, of me being somehow mad or delirious, and yet my artistic process of creating it is orderly and clear-headed. Maybe I am somehow reviving myself from some other state through the writing. On the other hand, the fictive, unfunny songs actually require me to enter into a delirium or trance in order to write them.

Anna Gallagher-Ross: Can you describe this state of working, this trance state?

JK: I might have a single phrase in mind, or a certain scenario—a person waking up in a strange place after some transformation or trauma, for instance. Or I might be writing from the point of view of three things at once—a baby being born, a scorned lover, and a mutilated creature. Or even from the point of view of a certain symbol or idea. It’s complicated! In any case, I am led by the language and sometimes a song becomes more of a game of language where the subject or speaker is kind of disintegrating or multiplying. Anyway I “labor in ecstasy” and I don’t really remember writing afterwards. The process erases itself.

AGR: You mostly work as a solo artist but have worked with collaborators in the past. At what point do you involve others in your process?

JK: It depends on the project. I like locating the limits of what I can accomplish myself. But I am continuously pushing and pulling on what those are. Generally, I cannot involve anyone in any medium until I’m done writing or at least until I suspect I might be done. This could take weeks or years for any given piece. I rely on collaborators for film work and also collaborate with people on music, especially in creating arrangements. I work with my trusted musical partner Dan Bartfield on string arrangements, for instance, and listen to his musical ideas and feedback on how I might elaborate or simplify my approach on piano, or how we might build an arc or change the feel. Or I might have a conceptual interest in turning a particular Monteverdi lament for solo voice into a choral piece and then, like a little angel-savant, musician Matthew Marsh can whip up something transcendent. My collaborator Laura Terruso has shot, cast, and/or directed or co-directed my videos. Her ideas and mastery is a key part of what made certain videos good. Lately my friend Chavisa Woods tours with me sometimes, with these concert-format nights, and she will tell me, “that moment was too private,” or “script that moment, don’t improvise it,” or “that moment really needs high-pop production values for you pull it off.”

AGR: The work you do straddles so many disciplines, and I hesitate to use the word “interdisciplinary” because I know that can be an unhelpful buzz word, so I wanted to ask you: what language do you use to describe your work?

JK: I’ve been grateful for the term “interdisciplinary” within the institutional world because it has given certain residencies and grants a context for me, and allowed them to support me. But I don’t lead with that term as I step out into the morning. It is very natural for artists to be expressive in a range of ways. Leonardo Da Vinci also played the lute very well—the big show-off. So in a way I find it quite odd, backwards, and bureaucratic to fetishize multiplicity when this multiplicity is in fact arising from a single impulse. Lately I have described myself simply as a singer and writer. I work hard on singing and writing. There’s a range of practices that take place “between” those two activities, but it’s in one way one thing to me—voice and language.

My only academic degree is in painting and I’m also somewhat aided by that visual sense, and informed by the types of thinking that go on in visual art. Here’s my beef: in our culture right now, despite flashes of originality, pop music, some classical music, commercial rock music, some of what is called experimental theater, strains of visual art, certainly commercial film are all marching on in a zombie state as imitations of themselves. I see in the cultural landscape a constellation of traps that must be avoided. So I must work in a way that feels natural to me, following my instincts, looking to tradition, balancing discipline with permission, examining my work from different angles and attempting to allow all the elements to have integrity, while not being beholden to a certain economy or social scene that surrounds one art form or the other. Resistance to categorical language may actually be one of my driving motives! This hasn’t helped with marketing but it has become part of what I do—again it’s become a language game for me, a dancing around, a tricky self-articulation.

But I am sick of being cut up like a starfish. I feel like this: a group of scattered limbs that are each trying to generate a new whole around themselves. I want to be looked at for what I am doing in its particularity, not asked anymore where I “fit in.” There’s a fracturing in the culture that I can no longer internalize.

BM: You just published a book. Can you talk about the writing that you do and how that plays into your practice?

JK: The book is something I’ve been working on for a long time. The earliest contributions are pieces I wrote when I was 20– I’ve revised them since. Half the book is new stuff, written exclusively for the page. The other half is material that has been performed or published in some way. When I first got to New York I was mainly working on these sort of “staged personal essays.”

BM: What language do you think in? Are your thoughts in writing or in singing or dancing, or a collage of those things?

JK: Lately my head converts any conundrum or question in my life into a colorful patterned form, which somehow reveals an answer to me, based loosely on how appealing or unappealing the shape is, and its temperature. There are different parts of your brain and your practice that you use at different times. If I have an idea, sometimes the idea might seem best as a song or performance or video, or I might not sure about the form it takes. I have many ideas that are purely conceptual: performance scenarios, durational situations etc. and often I never bring them into being because they don’t engage my skill sets. I’d like to open that up more—at Co-Lab Projects during my November visit to Austin I did an impromptu durational performance in the backroom, where I just spoke in the dark with one person at a time as we each reclined; so we became disembodied voices in a way. I did this because the curator Alyssa Taylor-Wendt had asked me to do something in durational form. But I’m sort of conservative, or maybe just a showoff, in that I feel I must always be exhibiting a cultivated skill. (I’m pro-virtuosity even though I also think virtuosity should be simultaneously undermined—that’s part of my aesthetic ideal.)

In terms of singing I don’t think of it as a language, but rather as what I imagine it is almost what dancers feel, where it’s almost a physical knowledge, a physical communication. I also identify with the strategies or approaches of visual art—portrait, landscape, and so on—but ultimately my abilities are more musical and text-based. And I’ve always had an uneasy relationship to objects and making anything that won’t disintegrate. As much as I like performing—embodying my work, and being its liaison, controlling its presentation—I have that great existential longing to create something outside of myself, something that could exist without me. Something someone could experience without my being there to facilitate it….

AGR: Could you tell us about your relationship to opera. How you first met, and how that relationship has developed since?

JK: I’ve always felt both inside and outside of opera. My experience of training as an opera singer, although serious, was somewhat removed because I was a visual arts student studying voice so my head space was always creative and I was passing into this other realm to cultivate a skill. For that reason, my repertoire was spotty and I wasn’t professionalized or trained to think of myself in the way an opera singer or an interpretive artist in a conservatory would. I originally loved blues and soul music. I wanted to be some kind of gritty balladeer, but then I started training vocally in order to gain some mastery over my instrument and I became attracted to the drama of opera and the heightened quality of it. So when I realized I had some talent in that area, and was encouraged to move forward with it, yet I realized that I didn’t feel comfortable in the culture around opera. I also thought going to endless auditions would be a punishing existence and the notion of it sort of offended me. At the time I was creating a lot of narratives and monologues and using really heightened language to give some sense of gravity and extravagance to the stories I was telling—which were almost landscape-like, with little narrative drive. And at the same time I was performing in this little opera house in New York and also making my own work and it seemed I could just synthesize my narrative work with this operatic technique that I was learning and achieve this sense of drama and a heightened state rather easily. So that’s when I began creating my own “arias.”

But always with my work I am playing on the edge: I am channeling an operatic sound but I don’t consider myself some great composer. I’m a songwriter creating relatively simple musical structures and sometimes a particular pastiche. I’m invoking “opera” through the composition, at times, and other times only through vocal production. And although I am now starting to do work in the opera world, up to this point, I have been mostly addressing a broader arts community and popular culture. I do like to ride those lines though. Just like with Let Me Die, the opera deaths piece, I have this scavenger approach to that repertoire and I’m taking different deaths and piecing them together in ways that are amusing or thematic or more conceptual. I’m performing different procedures on them. I’m treating the art form of opera as a character in history, as something iconic, thinking about the way it is thought of in the popular culture. I am often invoking the image of it, rather than the form itself.

BM: You are kind of an unofficial ambassador, because if people are meeting or showing an interest towards opera because of their encounter with you, why not?

JK: It’s true. I am allergic to belonging to one camp, but I also do want to be an ambassador, a liaison, in a lot of different ways. This isn’t a mission statement but perhaps an unconscious drive. Freedom, balanced with responsibility. That’s what I want in my art.

Click here for more information or to purchase tickets for an evening with Joseph Keckler on January 23 & 24, 2018, at The Long Center.

Photo Credits (in order of appearance):

-M. Sharkey Studio

-Hervé Véronèse

-Nick Williams