Selina Thompson on Race Cards

March 27, 2018

Selina Thompson is an award-winning artist based in Leeds who has worked across the UK and internationally since 2012.

Her practice is interdisciplinary, urgent, playful, and intimate – focussing on the politics of identity and how this defines our bodies, lives, and environments. With social engagement at its core, her portfolio of work is as strong as it is distinctive; spanning live work, installation, durational performance, intervention, writing, and visual art. Her work salt. has been presented to sell out audiences at the Edinburgh Fringe Festival receiving The Stage Edinburgh Award, The Total Theatre Award for Experimentation, Innovation and Playing with Form and the inaugural Filipa Brangaca Award for Best Female Solo Performance.Selina talks with Anna Gallagher-Ross and Betelhem Makonnen about the lived questions and experiences that shape her practice, as well the genesis and development of her work Race Cards which will be featured at the 2018 Fusebox Festival.

Betelhem Makonnen: For people who do not have familiarity with your work, how would you describe or introduce your work?

Selina Thompson: So when my goddaughter was five she described me as a show-off for money, and I’ve always enjoyed that as a description. But fundamentally I guess I am an artist that writes, performs, and makes installations. I’m trying to build up some other skills too, but I don’t have those yet, so we’ll leave it at that for now.

I make work about identity (at the moment) — about race and fat and beauty and being unemployed; about being a teenager; being a woman; being someone with a chronic illness. I’m interested in how these things change our lives, our societies, and how they call/come back to the body.

My work usually involves spectacle, it holds it together at its centre. My work is often playful, intimate, urgent and located firmly in the grey area of personal meets political.

BM: Could you tell us about your background as an artist and how you came to the arts?

ST: I did an English and Philosophy degree for a couple of years, and then I had a breakdown. I switched to English and Theatre – but my course was led by lecturers who were primarily concerned with the Avant-Garde — so we were looking at Dada and Romeo Castelluci, learning about Performance Art Festivals and making lots of messy, abject (terrible student) work… you know the drill –– lots of nudity and milk and food.

For my final dissertation I made a show called Chewing the Fat, which was a one-woman show about being fat, that had me sealing my body up with food and smashing piñatas full of rice pudding all over the place. I performed it at a little festival in Leeds, and some really supportive people in the audience encouraged and nurtured the work and me. The rest is history, really. So it’s an academic, rather than vocational background — learning as I go along, but with a foundation that is theoretical — and straight from university into making.

Anna Gallagher-Ross: Your work spans performance, installation, and participatory event. Could you talk about your interdisciplinary approach to making work and your influences?

ST: So I always wanted to be an artist, and to not be tied to any form so that I could make work that fit the subject. As opposed to exploring various subjects in the same form, if this makes sense? Interdisciplinary makes it sound so… I don’t know, so planned and clever, and I feel so inadequate when faced with that label! I just want to be as free as possible to make what I need to make, as and when I need to. And also from a place of… what’s the word — from a place of having no virtuosity.

Influences are — Bobby Baker, Scottee, Guillermo Gomez-Pena, Rebecca Sugar, Missy Elliott, Bryony Kimmings, Benjamin Clementine, Moses Sumney, Marina Abramovic, Lorna Simpson, William Pope L, Julie Dash, Stuart Hall, Toni Morrison, Grace Jones, Willis Earl Beal, Saidiayah Hartman, Maggie Nelson, Ellen Gallagher, Karen Finely, Laurie Anderson, Coco Fusco, Lorraine Hansberry, Marita Bonner, Lee Lozano, Dionne Brand, Suzan-Lori Parks, debbie tucker green, bell hooks, Sylvia Wynter, Frantz Fanon, Nalo Hopkinson. I am so, so fed at all times by other people’s art.

BM: In other places you’ve mentioned that Audre Lorde is a huge source of resonance and influence in your work. Could you tell us more about this?

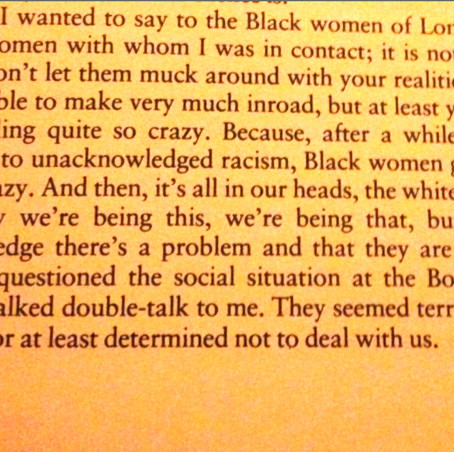

ST: Reading Sister Outsider (1984) changed my life. And that sounds like… it’s such an overused statement, and it’s a really big one, so it’s hard to take seriously, but it really, really did. That feeling of being seen, but also of being asked to be more! To be more rigorous, to work harder, in addition to the validation of, “I am not crazy, these things I have been noticing and feeling are real.” I remember finding this Audre Lorde quote especially, from Shabnam Grewal’s Charting the Journey: Writings by Black and Third World Women (1988).

Audre made me feel like I didn’t have to split who I was as a person — black, working class, queer woman — from who I was as an artist. She made me feel like my work could be in service to those that might need it. It’s not an influence I can definitively show you, it’s more a deep down in my soul thing. I have a picture of her in my flat. I look at it every day and it inspires, comforts and pushes me. She helps me — what’s the Lady Macbeth thing – screw my courage to the sticking place. Without the regicide.

AGR: Can you tell us about the genesis of Race Cards (2015), the work you’ll will be presenting at Fusebox 2018?

ST: I was mad. Solange, A Seat at The Table mad. So… everything was happening too quickly. Black Lives Matter in the US, but also similar (though distinct movements) in the UK and across Europe. Protests at Yarl’s Wood, Artists staging human zoos, their work being protested and withdrawn, and I was trying to learn and catch up, just furiously, reading everything I could, seeing and visiting and experiencing everything I could, just trying to have the language to articulate what was going on around me, and be able to deploy that language, trying to figure out how to be active and useful and what it was to live words like “intersectional” and “decolonized” and “radical” — not just say them.

So all this is happening inside my head and inside my private space — but at the same time as a black woman, there is an expectation that you will educate white liberal people — often older, and with far more resources than you have ever had, and I was sick of it, fed up. I’d gone to see a work that was withdrawn because it was deemed racist and offensive, and written a blog about my response. Every time I entered an arts space I felt interrogated. Every time I went online, I saw black women constantly having to fight and defend themselves. There was no space to just… just exist. And I was fed up. I wanted to have a conversation about race in which I completely controlled the terms of engagement. And I was going to ask the questions — and the white liberal arts audience were doing to do the thinking and come up with the answers. And I was going to grant myself the gift of some silence, some opacity. So that’s where it comes from!

AGR: Race Cards takes a different form each time. Could you talk about its many incarnations and what has shaped them?

ST: The first version I did at the end of a week-long residency in Falmouth. It was this very fast and furious card game — very nonsensical, a mish-mash of quotes from twitter and think-pieces and theory. Played against the audience. It didn’t really work.

The second time was as a theatre show. I did it at Camden’s People’s Theatre, and it was about half an hour long. I liked the simplicity of it – me in a black dress, one desk, the white cards on a black table, a tight spot light. It was very emotionally raw – but despite the taut quality that the aesthetic had, it was messy and unwieldy as work.

The third time I locked myself in a room in Glasgow, at a festival called Buzzcut, and the task was to get to 1000 questions about race in 12 hours. People could mill in and out. I got to question 727, I think. Then I was sick. I hated it. I felt like I was being gawked at, and the sheer volume of people in the room ruined it as a space for contemplation. When people feel uncomfortable about and around race, they tend to have performative actions that they fall back on, which are often problematic. There was a lot of that in that room.

The fourth time was at the Edinburgh Fringe Festival. I gave myself 24 hours, split into 3 eight hour shifts. People could come into the room one at a time. I liked it a lot — but I was still really sick afterwards. It’s like a big purging. I said I didn’t want to be in it the next time it went out, that I wanted to be an installation.

The fifth, sixth, seventh, eighth and ninth — maybe more — time it went out as an installation without me. Arts spaces, university spaces, festivals and libraries. I don’t see it when I’m not there – it’s too hard for me. Like seeing your limbs spread out across a room for other people to inspect. I find people’s response challenging all at once — so many voices!

This year Race Cards will go international. Texas, Toronto, maybe Germany twice. I’ll also be doing a reading of the questions, something I did last year in London. It kind of knocks me out, doing that reading. In Austin and Houston, I’ll also write some questions in response to the context that I find myself in – because there is a… a something — tension? I’m not sure — but there is something about being a Black British Artist making work in an American context when our countries have different relationships with race — like they’re siblings, but still different. So something that acknowledges that, and hopefully fosters solidarity.

The different versions of Race Cards are shaped by self-care, curiosity, and the constant shifting of my perceptions of race, and the world around me in relation to race.

BM: Race Cards is described as an archive and also the research for the larger body of work As Wide and As Deep As the Sea. Could you speak about the role research plays in your work, and also about this larger project?

ST: It’s definitely a research led practice — like I’m sure my list of influences betrays me, I am a reader first and foremost. So there’s always a long time spent reading and going to conferences and connecting with academics and trying to make sure that the work is intellectually rigorous.

But also fundamentally, the work has to connect to an audience in a way that is compelling — so there had to be research that enables it to do that — so I always want experiential research, and also a lot of conversations that are happening with the communities that the work is made for, or about or with. So sometimes that manifests itself as working in hairdressers and beauty supply shops for six months, other times gate-crashing weight watcher’s meetings with biscuits, or, as was the case for salt, doing a two-month research trip to Jamaica and Ghana, travelling via cargo ship. Research is central. I think the bolder and more challenging a research process is, the better the final work.

As Wide and As Deep As the Sea is about Blackness, in a British context, but also more broadly, in an international context. I group my work into bodies like this because it just helps me be able to see it more — helps me find the connections between pieces of work, and also know that salt. (2017) doesn’t have to do it all — that Race Cards can do some of it or Dark and Lovely (2014) can cover another part. It’s also part of that whole — what are the multiple forms for exploring and exploding this multiple thing?

xxx

Photo Credit: Manuel Vason