Wunderbaum on The History of my Stiffness

April 16, 2018

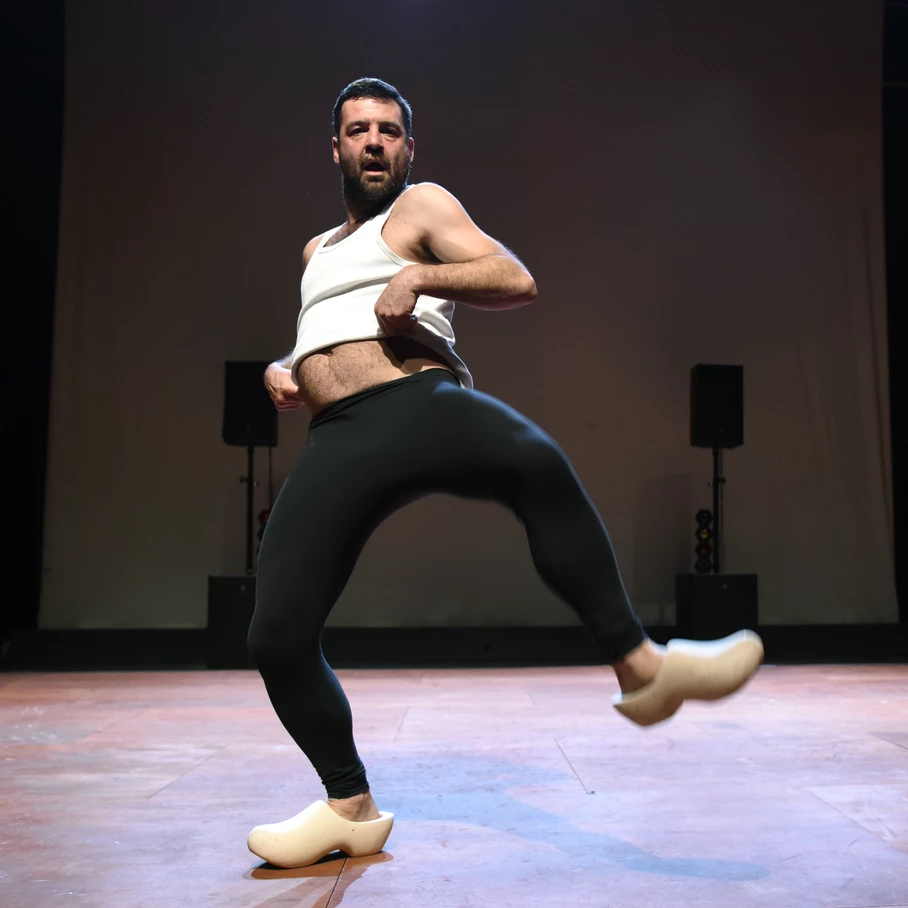

The theatre collective Wunderbaum was formed in 2001 in the Netherlands, by actors Walter Bart, Wine Dierickx, Matijs Jansen, Maartje Remmers, Marleen Scholten and designer Maarten van Otterdijk. The collective creates works exploring disruptive questions that emerge from everyday reality, frequently on site, but also in theatres. They have performed to audiences word-wide, among others the United States, Iran, and Brazil and are the recipients of numerous awards, including the Mary Dresselhuys Award, the Total Theatre Award of the Edinburgh Fringe Festival for the work Looking for Paul (2014), as well as the VSCD Proscenium Award for their entire oeuvre. Fusebox 2018 will feature the world premiere performance of Wunderbaum’s latest work, The History of my stiffness. Walter Bart and Marleen Scholten speak to Fusebox artistic director Ron Berry and curator Betelhem Makonnen about this hilariously serious new piece as well as their practice at large.

Ron Berry: We’d love to hear about your origins and how you started working together.

Walter Bart: We met in theatre school in Maastricht in 2001. The Maastricht Academy of Dramatic Arts started the tradition of “theatre making,” meaning in addition to acting, you make your own theatre. We met in a class and we liked working together, most specifically site-specific work. We always made work outside of theatres because we wanted to get ordinary people to the theatre. In the beginning, that was our main goal to make work that for people who don’t normally go to theatre, special places like town halls and community centers. Later we expanded into other disciplines, started adding music by working with a lot of musicians.

Marleen Scholten: In a way, this is why we like to work with what we call “the real people,” or the participants we put into our shows. Aside from just liking to work with them, they also bring their families, their people, to the shows. These are people that don’t often get to have contact with our work. We still try to step out of the theatre reality.

RB: Can you talk a little bit about how you think about making theatre? When I think about your work the question of representation within a theatre context comes to mind for you are often playing “yourselves.” There is always a play between fact and fiction and reality.

WB: Very often playing a character does not feel direct for us. We want to use ourselves as to have a direct line to what we have to say, by starting with our own world and out of this world we can start to build up a fiction. We start with our own experiences and material to form the characters.

MS: We also try to never be above the characters and say that “this has nothing to do with me because I am a very big character, and this is very far away from me.” We always look for some kind of transparency and vulnerability. Let’s not pretend that we have nothing to do with these people but that we are these people as well. I think that this personal layer is always something that we try to put in so we don’t make the work something ironic, where we are just laughing about other people. Let’s laugh about ourselves.

WB: We start a show a lot of times by saying to the audience, “welcome to our show.” We want to make sure that the audience and we are in the same space. So that we don’t build a fiction and there isn’t a fourth wall where we are on the floor and the audience is sitting there. It’s that kind of strange situation that we have with theatre, where we have this understanding that you shut up and we do something for you. We want to be sure that everyone is on the same starting point.

BM: I love the fact that you use humor and absurdity so well in your work. Has that always been a feature of your work?

WB: We really like shows where we can also laugh. We always wanted to give people good time.

MS: For me, it also because we always try to use political and social issues and also use themes that are not so light in themselves, so for us the best way to tackle this is to bring it with a lot of humor and be open about it. Not that we make it ridiculous, but not to be moralistic. It’s our way to not say, “Ladies and gentlemen, this is the message.” That’s not who we are, I think. The message itself is real but always grotesque or absurd, with a lot of fun for ourselves and the audience as well. We like people to laugh.

RB: How do you work as a group? How are the decisions made and does it vary from show to show? Is there a Wunderbaum process?

WB: Every show has a different process. A lot of times it starts with us talking. We talk a lot. We first talk about a concept that we all feel good about and then decisions are made together. We believe that one idea is always the best idea if you talk long about it and convince the other. We work on the floor a lot. We make a lot of our own material and we also know what it feels like to it because we immediately put our ideas on the floor. So, if it doesn’t work, you immediately feel it. If it doesn’t work, we throw it away and we try something else.

MS: The processes can differ because sometimes we work with all of us and other times we work in twos. The basis is always collective and organic.

RB: Will you speak about the project you will be premiering at Fusebox 2018, The History of my Stiffness?

WB: The start of it is very political but the outcome is definitely not, which might be something weird about it. In Holland right now, there is a lot of talk about –– What’s Dutch? What are Dutch traditions? Who’s Dutch? –– I think it is part what is happening everywhere, same as in the States probably. They are also debating whether Dutch children should learn the Dutch national anthem. For you maybe it is not so weird because I think the American anthem is pretty much part of your culture. [laughter] Or not?

I think it is different even before under Democratic presidents … or not, I don’t know. Like with the America flag. I think Dutch people are always ashamed with their own flag because nationalism in Holland is another kind of nationalism. I don’t know … we are kind of ashamed for being Dutch but now they are telling kids in school that they have to learn to sing the anthem. So, we started asking a lot of questions, “what’s Dutch?,” “what’s this Dutch tradition?,” “what’s this Dutchness?” And what we came up with, which everyone really knows about, is wooden shoes. So, we thought, let’s start with these wooden shoes and see what this is all about.

BM: So, in relation to the “stiffness,” was this stiffness in the whole group or were some members stiffer than others?

[laughter]

MS: We are definitely two of the most stiff ones. [laughing] That’s a really funny question. I think the idea started for us also as a metaphor, right? Are we going mentally in a very stiff and conservative direction? Shouldn’t we be really worried about this? And, also analyzing our own bodies and knowing how we move on the dance floor. It is funny and also quite shocking. I mean, we are really stiff. The Dutch are stiff and there is nothing to do about that. [more laughter]

WB: It’s funny, I discovered this book about American dance. It says that Mr. and Mrs. Henry Ford promoted old-fashioned dancing at a certain point in the States, because they wanted to protect the culture.

BM: I wonder what they were referring to as “old-fashioned”?

WB: I think it was something like quadrilles … playing quadrilles? And they were really against jazz and jazz dancing. I’ll bring the book. I was really surprised that Henry Ford was protecting what I think is mainly the White American culture and saying that this is what we want and that jazz is evil and bad. It is really bizarre and also the book is called Good Morning — After a Sleep of More Than 25-years Old-Fashioned Dance is Being Revived by Mr. and Mrs. Henry Ford. It’s published in 1926 in Michigan. Using “traditional dance” as another way for people to refer to their identity seems very bizarre to me.

BM: Do you actually use clogs in this performance?

WB: Yes, the whole time. It’s fun to use them because they are really loud, and the sound is good.

RB: What was your relationship to clogs prior to this performance? Did they play a prominent role in your childhood?

[laughter]

WB: Yes, yes, of course, as a kid, I had them.

MS: I never wore them actually. You had them?

WB: Yes of course. I had the clogs and they were very handy for working in the garden and …

MS: We discovered that they keep your feet very warm.

RB: That’s a good feature.

BM: Did you find that there is a resurgence of clogs with increased conservatism? Do you think that people are wearing their clogs more now?

RB: Yea, should we buy stocks in clogs?

[laughter]

WB: No, I don’t think so but there is a real weird thing going on, where everyone is really proud of the seventeenth century again. This is the time when Holland invaded other countries and forced people on ships. It is really weird to become proud about this part of our history.

BM: It is like the 1950’s here in the US.

WB: Yes, the same. They say that the 1950’s are the times to get back to.

BM: The best of times, but for whom is the question.

WB: Exactly.

RB: The picture of “traditional America” in advertisements is what they are longing for.

WB: Yes, exactly. So, we will end the performance in “traditional” Dutch costumes which we will bring with us. You will see them.

[laughter]

RB: We are super excited and can’t wait to experience this show. Thank you for taking the time to talk to us about it as well as your practice in general.

WB: Great, we are excited as well and very much looking forward to being there.

MS: Do you have some stiff people that want to join us?

[laughter]

Photo Credits: Daniel Cohen (first image), Sofie Knijff (second and third image)