A Short History of █Redaction █

February 27, 2020

From Johannes Gutenberg to William Barr

On a blustery morning in 14th-century Mainz, the printing press was born. Though the first mass distribution of text was the Bible, within a generation Johannes Gutenberg’s invention was being used to spark the continent-wide insurgency against the Catholic Church, via the printing and distribution of Martin Luther’s critique of the institutionally corrupt oligarchy, which was prohibited by by the Holy Roman Empire. As we know, the story of printed text is a story of the power to distribute text, and the power to censor it.

Redaction carries a broad range of historical meanings. Derived from the French, redaction has been used to describe the process of creating, synthesizing, and editing texts; rédaction continues to be used in a more general sense in French, where it is roughly synonymous with any type of textual editing. But in English, the more specific use of redaction as a form of censorship, is relatively recent.

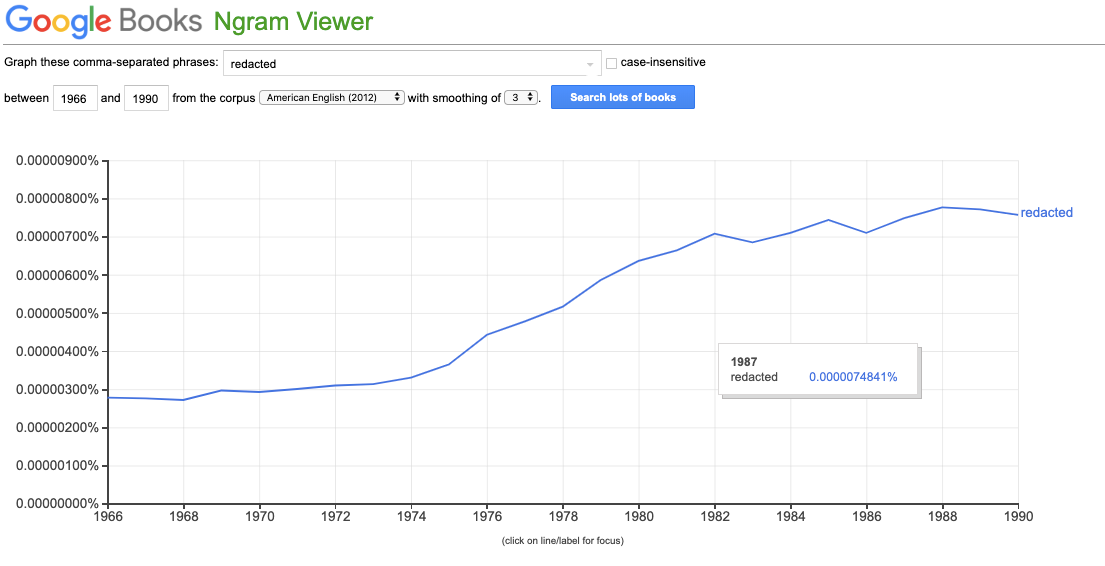

Redaction acquired its contemporary English-language meaning in the 1960s: redactions modify texts by obscuring elements of the text while making those obscurations visible. The rise of redaction in American legal proceedings largely coincides with two trends: (1) the rise in prosecutions of organized crime, which relied on testimony from witnesses whose identities needed to be concealed to protect against retaliation, and (2) the proliferation of publicly released documents mandated by the Freedom of Information Act of 1966. In both of these cases, redacting portions of texts allowed the government to comply with strict legal requirements about public testimony and public production of documents, while still concealing names and facts when the state wished to do so.

When evidence of widespread criminal conspiracies was revealed during the second term of two successive Republican presidencies—Nixon’s Watergate in 1972–74, Reagan’s Iran-Contra in 1985–87—the use of redaction as a means of avoiding disclosure of criminal conduct by government officials became widely known: uses of “redaction” in the Google Ngram nearly tripled between 1968 and 1988.

Redaction is a subset of censorship, of course, but while all redactions are censorship, not all acts of censorship are redactions. When documents disappear from public view or are altered to appear to be originals, the alterations are intended to pass as originals. For instance, when the Soviet archive proto-Photoshopped Trotsky out of official party photographs, it took care to make it appear that he had never existed. However, in contrast, texts that contain black bars, scratch-outs, and visible scissor gashes evince the mark of redactions: acts of censorship that are transparent in their opacity.

Lenin’s speech (1919). Original photographer: Grigory Goldstein. Image retouched under Stalin (year unknown).

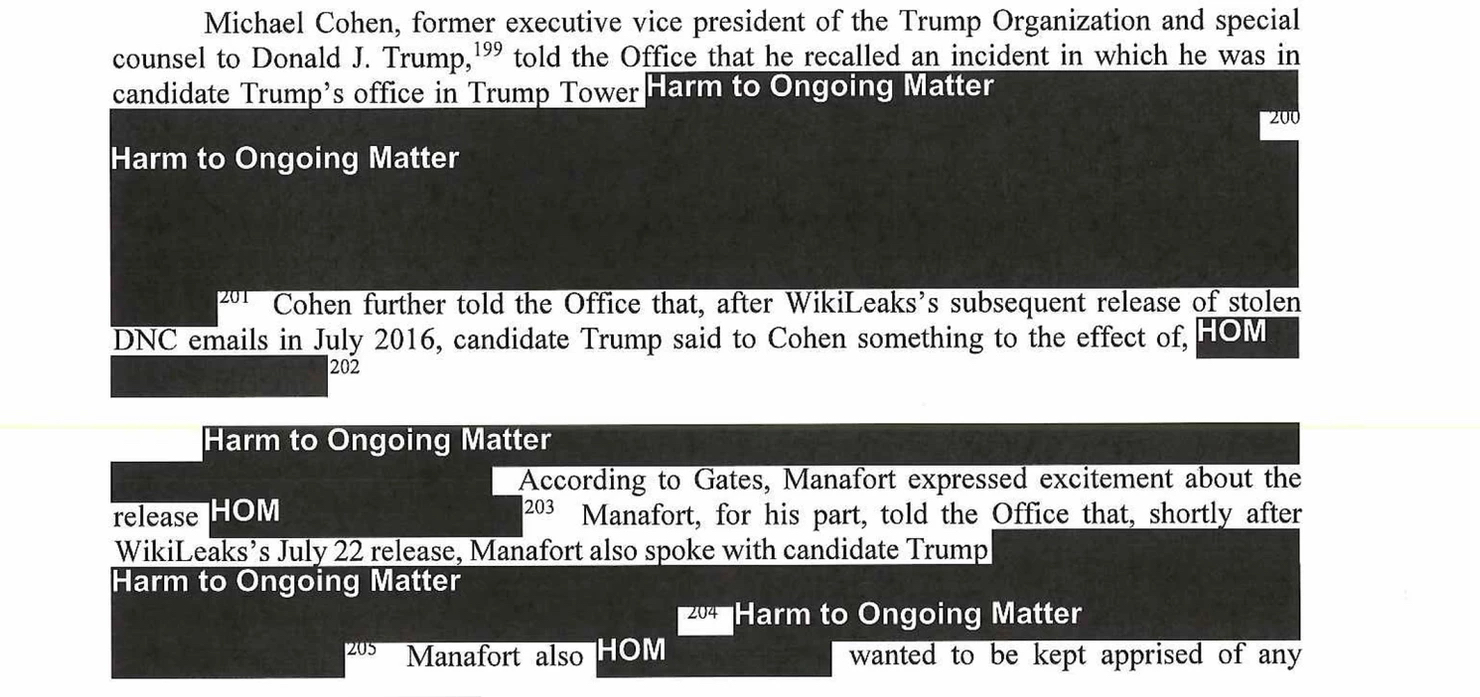

Indeed, the mechanisms of government redaction work differently. A century after Soviet-era “deepfakes” when Attorney General William Barr released Robert Mueller’s report on Russian interference in the 2016 election, the multicolored bars obscuring large portions of the text call our attention to the censor’s hand. We can’t see what’s behind the bars, but we know that there’s information being withheld. [1] (Barr famously characterized the released version as “minimally redacted” although at least one redaction appears on 40% of the pages in the report.)

Excerpt from The Report on the Investigation into Russian Interference in the 2016 Presidential Election (commonly known as the “Mueller Report”)

We can see that redactions yield hybrid texts, where the ink of the black boxes and the ink that arranges letters and words open multiple ways of seeing and of reading. But it is not only the medium that has become hybridized—part words, part black boxes—by the redaction. These texts are hybrid versions of public records: partly revealed, partly concealed. We have access to government oversight in part, but only as far as the state permits us to see.

(Redacted texts predate the 1960s, of course, as they more frequently took the form of crossed-out wartime letters and censored government disclosures. Slavoj Žižek retells the Soviet-era joke about the slippery nature of government censorship, where the man traveling into Siberia tells his German friends that he’ll write to them in code in order to get around the censors: his letter will relate true information in blue, false information in red. When his first letter arrives, his friends tear open the envelope. The letter, written entirely in blue: “Everything is wonderful here. Stores are full of good food. Movie theaters show good films from the West. Apartments are large and luxurious. The only thing you cannot buy is red ink.” The text simultaneously tells and untells us the truth.)

From Charlotte Brontë to Jenny Holzer

Artists of all disciplines have drawn on this tension between what texts can and can’t transmit. Laurence Sterne’s novel Tristram Shandy (1759-1767) famously depicts a black page; Victorian novelists such as the Brontës frequently redacted proper names due to broad libel laws. [2] For instance, the redacted county name (“____shire”) in Jane Eyre is certainly Yorkshire from all textual evidence, but authors and publishers redacted such names in their well-founded anticipation of libel suits. [3]

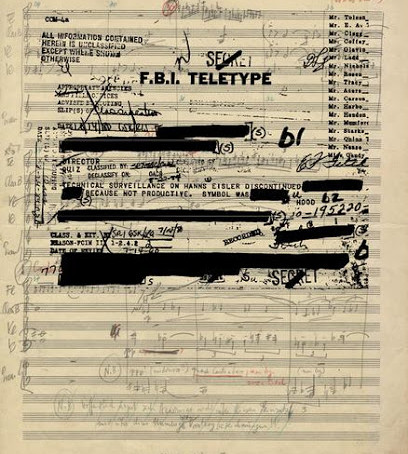

Contemporary visual artists such as Susan Philipsz and Jenny Holzer have depicted the redacted documents of the modern US security state in their work. Philipsz’s 2014 installation Part File Score examines the composer Hanns Eisler, an emigré from Nazi Germany who settled in Los Angeles, only to be blacklisted by Hollywood and investigated by the FBI as an alleged communist sympathizer. The installation overlays fragments from Eisler’s unfinished scores onto reproductions of redacted pages of his FBI file, linking the dual persecutions by McCarthyism in the private and public sector. Each print functions like a palimpsest, showing multiple layers of marks: music notes, notes from his FBI dossier, and black bars that obscure both. Here, the artist shows how the hand of the state overshadows his professional work product and his legal status as a refugee.

Detail from Susan Philipsz installation Part File Score (2014)

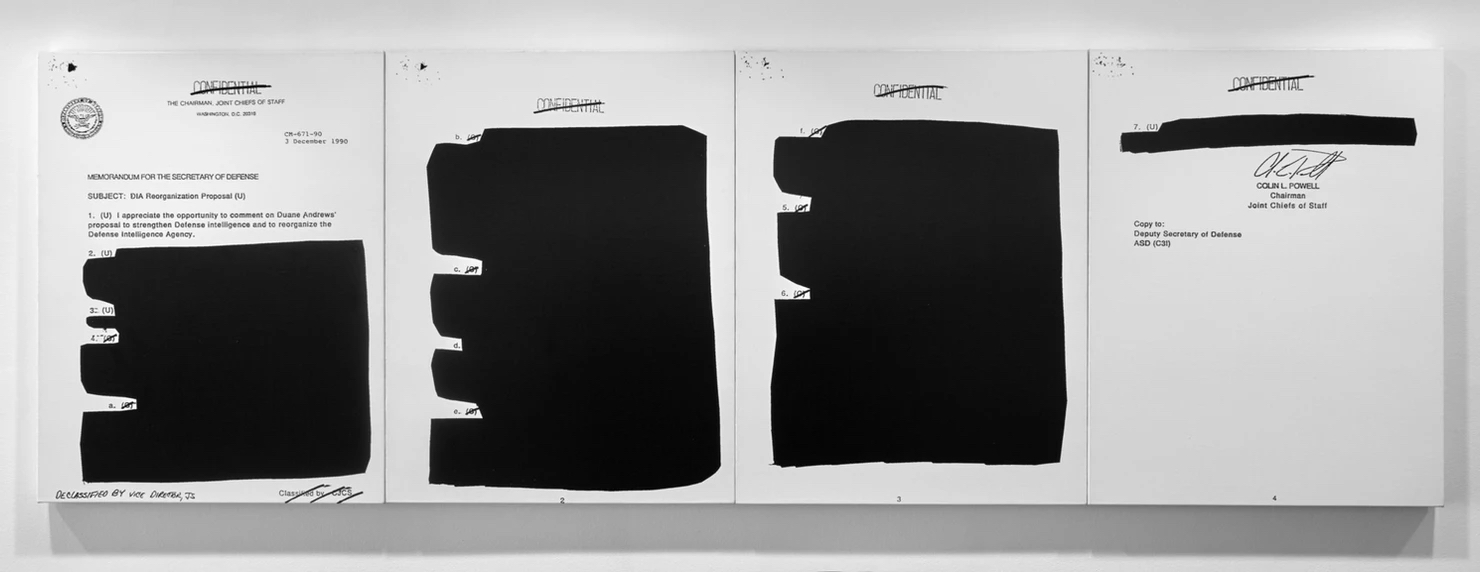

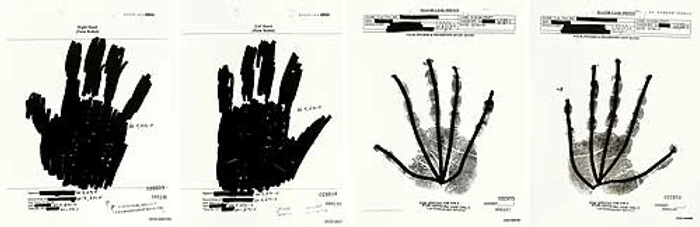

Holzer’s series Redaction Paintings, begun in 2005, repurposes declassified documents from the invasion of Iraq into large oil paintings. Some works in the series rearrange blacked-out portions of these documents, which range from communiqués among high-ranking members of the National Security Council, to lower-level reports about torture of detainees. One recurring image in Holzer’s rearrangements is for the black bars to suggest the shape of a human hand, as if a gho(a)stly spectre. Other works in the series present the documents relatively faithfully, where the only alterations to the text are the media—from pixels to oil paint and linen—and the scale, as most of the paintings are several feet tall and tower above the viewers in the gallery space. It’s a series that is continuous with themes in Holzer’s previous work, decontextualizing and re-setting text in new contexts, but one that asks audiences to consider what it means when a government kills hundreds of thousands of people and refuses to disclose how or why it happened.

Jenny Holzer, Redaction Paintings (2005-ongoing), The Chairman Joint Chiefs

Jenny Holzer, PALM, FINGERS & FINGERTIPS (RIGHT HAND) 000394 (2007)

From Reality Winner to Is This A Room

Because the modern era of textual redaction typically deploys black bars as the primary method of censorship, it’s tempting to look to two-dimensional rectangular art objects when we think about redaction in art. And indeed we have fewer examples of how three-dimensional and time-based artworks approach the subject of redaction. For Austin audiences, one compelling exploration will be presented by Fusebox Festival in April 2020.

Is This A Room, a 60-minute performance conceived and directed by Tina Satter and performed by her theatrical ensemble Half Straddle, adapts the redacted transcript of the interrogation of Reality Winner, a veteran of the US Air Force and foreign-language translator who was arrested in 2017. She was swiftly charged, convicted, and sentenced to 63 months in federal prison for the crime of distributing to the online news publication The Intercept a classified report detailing Russian hacking of US voting registration systems in 2016.

The transcript itself, of the interrogation preceding Winner’s arrest on June 3, 2017, seduces its audience into believing in its own transparency. The text records its “stage directions” with maximum detail. Every laugh, every throat clearing, every word of small talk left in. We learn the characters’ CrossFit routines. The color of their guns. The weather in Minot, North Dakota. Their dogs’ barking rhythms.

But the text redacts everything about how the alleged crime took place, everything about the subject of the alleged crime, and any discussion of what punishments lay ahead and why. (Curiously, the transcript does make clear by omission that the FBI agents failed to advise Winner of her constitutional right to remain silent, which was the subject of an unsuccessful appeal of her conviction.)

Is This A Room, the performance, cannily implicates its audiences by presenting the redacted portions of the transcripts with translucent staging: the disruptions within the actors’ delivery and the visual appearance onstage are both brief but unmistakable.

When I spoke about the performance with Satter, she identified two different approaches used for representing redactions: for basic factual information, the actors are instructed to pass over the omitted text quickly. These omissions are presumably relatively immaterial omissions, ones that are redacted to protect privacy but that aren’t central to concealing the larger workings of the national security state—like birthdates and social security numbers.

Is This A Room at Mladi levi Festival featuring Becca Blackwell, Frank Boyd, TL Thompson, and Emily Davis. Photo Credit: Nada Zgank.

But the material omissions from the transcript—the facts that led to the publication of Winner’s leaked document and that led to her receiving the longest sentence ever imposed for releasing government records to the media—are presented as disruptions to the aesthetic continuity of the performance. Deep bass chords punctuate the otherwise sparse sound design. The lighting pulses, reminiscent of lightning strikes or power surges. In Half Straddle’s monochromatic production design—which one critic analogized “as a flat and narrow redacting stripe”—the interrogation itself is presented through a relatively desaturated color palette, while the moments of redaction are awash in pink.

Is This A Room at Mladi levi Festival, featuring Frank Boyd, TL Thompson, and Emily Davis. Photo Credit: Nada Zgank.

The effect is much more moving than a straightforward blacking-out of the performance space. The lighting cues evoke a mysterious, haunting presence—these redacted moments where we simply don’t know what was said are spectral, like Holzer’s handprints. For a play with the full title Is This A Room: Reality Winner Verbatim Transcription, the climactic moments of the “verbatim transcription” are the pregnant spaces between, the gaps in the record, or the moments when the transcript ends, which prompt us to reconsider what we’ve witnessed. If the power of the prolonged interrogation is horrifying, we can only imagine what happened that the recording can’t tell us.

As we’re reminded on a daily basis, government corruption and textual redaction are close cousins. While government officials praise themselves for disclosure and then cloak those disclosures in redactions, the printed black boxes on these texts remind us that our governmental agencies don’t believe they’re accountable to us. The searing politics of works like Is This A Room remind us that redactions are far too easily and too frequently used to conceal injustice. As in the case of Reality Winner, the initial concealment—the Trump administration concealing evidence of Russian interference on his behalf during the 2016 election—is draped in a second layer of concealment—the redaction of the full transcript of why Winner was imprisoned. To learn why she’s incarcerated in a federal detention center in Fort Worth until the end of 2022, is to learn the limits of our own freedom to speak out against government officials. Though the consequences can be severe when we do, they’re even graver when we don’t.

ENDNOTES

[1] Judith Butler persuasively argues in Frames of War that we should understand all transmissions of government information to be censored, since we can never know which information has been withheld, even when a document is purported to be unaltered: “we cannot understand the field of representability simply by examining its explicit contents, since it is constituted fundamentally by what is left out, maintained outside the frame within which representations appear. We can think of the frame, then, as active, as both jettisoning and presenting, and as doing both at once.”

[2] In these texts, redaction functions at the behest of the market rather than the state.

[3] The fact that women novelists would frequently use male pseudonyms when submitting to publishers—Jane Eyre was originally published under the name “Currer Bell” rather than “Charlotte Brontë,” for instance—reinforces the power of the market to efface the text, beginning with the title page.

Adam Bennett is a writer, lawyer, and curator based in Austin. His program Slow Looking appeared at Fusebox Festival in 2018, and he has co-produced Fusebox programs with Deborah Hay and Suzanne Bocanegra.