Alan Garcia and His Digital Museum of a Disappearing East Austin

October 5, 2017

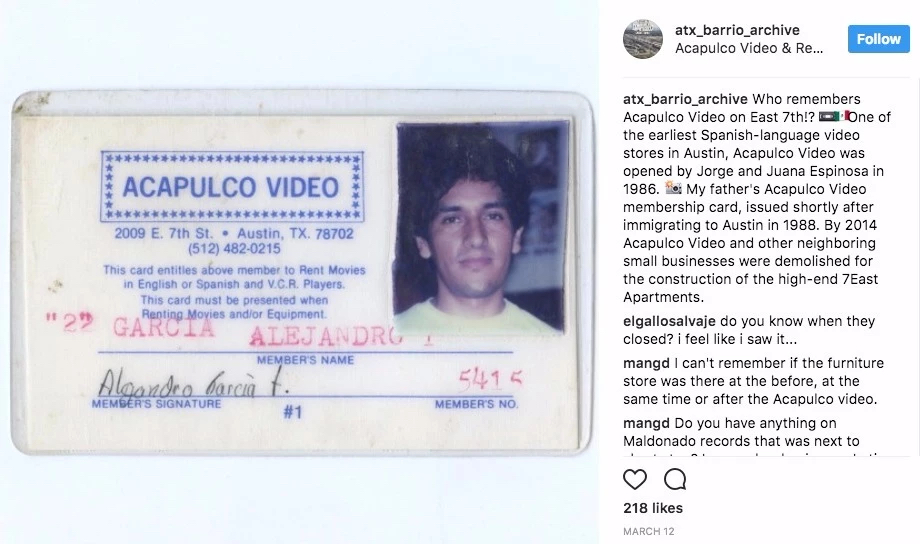

In July 2016 Alan Garcia created the Instagram account ATX Barrio Archive to showcase the visual cultural history of Austin’s Eastside

barrios. Alan began with images and stories from his family’s experience immigrating to Austin and materials uncovered through his research in city and university libraries, but soon began receiving images from people who wanted the stories from their community told. As we reconsider our country’s historical monuments and the types of histories we give precedence, ATX Barrio Archive provides an alternative: an accessible digital archive that documents the history of a neighborhood and its people. Ron Berry and Anna Gallagher-Ross sat down with Alan to discuss the origins of the archive and the urgent need to document this history that is rapidly disappearing.

Ron Berry: Where did you grow up?

Alan Garcia: Mainly in south Austin. When I was born we lived off of Burnet Road and North Loop. My family had an import business, textiles and such. It was pretty affordable back then. On weekends my family and I worked at the flea market on Highway 290 in Northeast Austin. We sold soccer jerseys, jewelry, electronics, etc. That’s where we became friends with a lot of East Austin families and business owners.

RB: Can you tell us a bit about how this project came to be?

AG: It started with material I had from my family’s archive. Growing up my mom was the main scrap-booker and videographer. Looking back on it now, our family history is preserved on all of these fragile, at-risk formats, like VHS tapes or rolls of film. My parents immigrated to Austin in the 1980s, so there’s family history from back in Mexico, but the family history in Austin is summed up by these VHS tapes and disposable camera pictures. My intention was to digitize these materials and share their experiences as immigrants in Austin because even during the years before I was born, the city that they first saw, that they lived and worked in was and still is constantly changing. Before the Alamo Drafthouse Cinema was on South Lamar, there was a grocery store my parents shopped in. They lived right there in Stoneridge Apartments, which were torn down and replaced by condos. The spaces my parents lived, the cultural centers that they experienced, wouldn’t have been there if not for the people before. By telling their story, inevitably it led me to share the story of generations who came before them.

I’ve always been a history nerd and a library nerd and I’ve always found that the Austin history that exists is very downtown-centric, very top-down. It’s a history that deals with who was governor, Lyndon B. Johnson, the Zilker family, the Pease family, the Driskill family. I love that history, it’s still our story, but it’s not my family’s story. There’s plenty of coverage on the European immigration but I wasn’t seeing the stories of the people who worked in the hotels, the restaurants, the night shift people. So the Instagram account was a way to put it all in one spot, make it dedicated to that history. And it partly is born out of this frustration, seeing so much getting lost, without being documented. If I don’t do it, I don’t know what it will be like 50 years from now, when we are trying to figure out who was there, what was there. So I saw this Instagram account as a way to share immigrant experiences of Austin that doesn’t get a lot of exposure.

Anna Gallagher-Ross: Where do you source these images from? It began as a personal family archive, but can you talk about how it grew from there?

AG: It’s grown a lot. Half of the material I discovered in my research in archives—at UT Austin, the Austin History Center—that are related to this history of East or South Austin. Much of it is old newspaper clippings, yearbooks, unpublished academic theses—forgotten material. Although these archives contain materials that relate to these neighborhoods, these images of industrial landscapes, unpaved streets, poor neighborhoods are not their priority, and so none of it has been digitized. Putting this material online allows people to see it, to access it. The other half of this research is outreach. People coming forward and sending stuff to me, sharing photos, meeting with people.

RB: What we need is more affordable space in Austin. The term “affordable space” gets thrown around a lot, and it means different things to different people, but there is a real need. And there are clear mechanisms to getting at that, whether there is actual will is another matter…It does feel like there are less clear mechanisms in place to help smaller, family-run commercial businesses. That’s where so much culture and coming together happens in our communities and so along with housing, these small businesses—whether a music club or a restaurant or a bakery—have been the other loss. Those spaces have such meaning. It is such a crisis—preserving meaning in all kinds of ways.

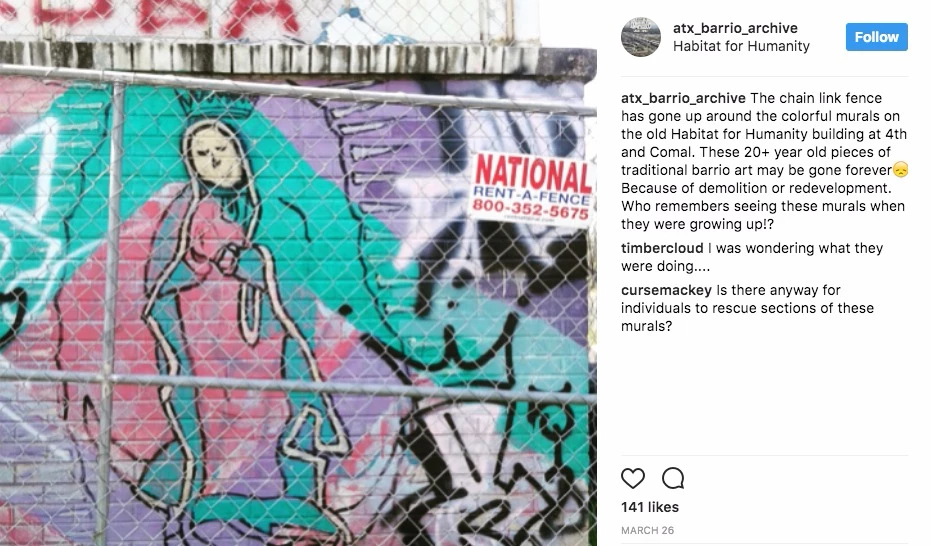

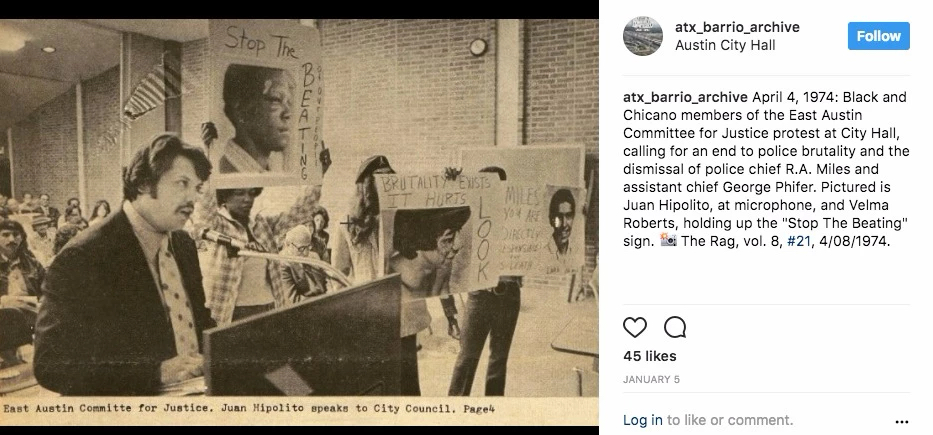

AG: It seems that at the municipal level, even at the Historic Preservation Office, it’s hard for them to cross that barrier and say, “we need to preserve this.” They tore down the Habitat for Humanity warehouse on Comal, right across from Chalmers Courts. There were murals on that building from the 1990’s that had been painted by neighborhood children at a time when Austin coming out of an era of gang violence, when community leaders knew tagging was a problem and wanted to create something positive for the neighborhood. Those murals featured low-riders, Aztec imagery, African drummers, music, breakdance culture, images related to housing activism and the philosophy of recycled materials. But when you read the documents of the historical associations of that building, the records only speak of the businesses that were there, or the fact that it was an industrial building and worth saving because its pre-World War II and rare, but there’s no mention of those murals. The people making these decisions are blind to what is barrio culture, what deserves to be preserved. And on the East Cesar Chavez strip, what used to be a blues joint, what used to be a tejano bar, but ever since, there’s something new. I always think; there was something there before, people that had names, it wasn’t just a joint. The piñata store that got torn down, I mean, that’s a craft. But developers and city officials are blind to these things. To them it is not worth saving. No one is there to argue: “this has value, this is from the Stop the Violence Movement, this is from the Golden Age tejano music, this is the blues history of East Austin, and now they’re all gone.

AGR: It seems so politically important that you are not only including images of protest movements and activism but you are also looking at everyday moments, families, what it looked like on someone’s front porch. That blend of images feels really important to creating an alternative history.

AG: I am really interested in the everyday stuff. What Rainey street looked like in the 1980s, and ‘90s, when yard art was such a big part of that neighborhood. And even before the Mexican Cultural Center was on Rainey street, there was a museum called Museo del Barrio, just off Cesar Chavez. A group of people made up of grads from UT and East Austin community leaders, artists, educators rented a space and opened up their own museum that offered arts programs, folklore dance, and also access to history. Photo essays about Rainey street, a tour of East Austin yard art, Catholic shrines, decorations that you wouldn’t find anywhere else, and now I cringe to think about these properties and what’s happened to them.

RB: Rainey street is particularly brutal. It feels violent what’s happened to those properties.

AG: Yeah, and what’s happened to civil rights history, too. That was stuff I had to find out on my own. There is never much mention in official history books or even monuments that talked about the fact that, for example, this is where Martin Luther King desegregated the Texas Union Building at UT because he was invited as a speaker. And I don’t think anyone knows that when he visited, he wasn’t permitted to stay at the Driskill Hotel or at any hotel downtown—this was the early 1960s—and so he had to just stay in some room, on a mattress. Those details are important. I mean, all throughout the South they have these civil rights trails, Selma to Montgomery to Birmingham, and Austin played a part in this history, too. Austin hosted Cesar Chavez in 1968. Chavez ate at Joe’s Bakery in support of striking furniture workers. This history is 50 years old. Any property that is 50 years old should qualify for a historical marker, for preservation. But in Austin, no one shouts it, no one erects any monuments. and so if no one else will do it, I’ll do it.

RB: What has the response been like?

AG: The response has been overwhelming. The goal was that one day hopefully someone will recognize their family members, and reach out to tell their stories. I posted a video interview of Roy Velasquez Sr.who founded Roy’s Taxi in East Austin during the Depression that provided taxi service to blacks and Mexican-Americans. The Velasquez family is still here, they are still community leaders, and so after posting this interview, I had members of that family reach out within minutes. Other people have recognized the business that their grandparents started or houses their families lived in. We also recently did a display at the Carver Library of images of the East 11th and Rosewood neighborhood and the incredible blues heritage. It was just this small installation in a window space for one month but people picked up on it, they got excited. I’m just happy that more locals, more long-time residents are learning about it and wanting to share.

RB: It’s an amazing project. And I love how it plays out on this personal, family-to-family level; it’s both hyper local but also has these global ramifications.

AGR: There’s something so democratic and accessible about Instagram. I think this project could be a model for other cities, in thinking about creating these monuments to these histories. I’m wondering if it were text, whether it would resonate in the same way. Do you think imagery is better at capturing people’s imaginations?

AG: I haven’t lost faith in the official ways of documenting or presenting these histories, but it’s slow, and it takes a long time for these institutions to catch up. There’s this online database of Texas history called The Handbook of Texas Online and people can volunteer to write scholarly entries about art, industry, people and, places. I thought about the fact that there are so many businesses on the East side that are worth mentioning, places that existed for 40 years, and so I submitted a short one on this business called El Porvenir on Santa Rita Street that had been there forever. All the museums in town like the Mexic-Arte museum, La Peña gallery, and even schools would purchase pan dulce, candles, and traditional herbs from El Porvenir to use for Dia de los Muertos exhibits and alters. The owner Rudy Castañon, aside from being a charitable business owner and community leader, was the neighborhood expert on herbal remedies. But their response was “thank you but this is too small, too local, this doesn’t have a big enough impact.” They were looking for State impact, people related to Congress or Texas legislature or the history of a big brand like Frito. And though these stories aren’t important to the officials, anyone on the street, anyone at the bus stop would say that these things are crucial to the barrio history. The only way for this to exist is through word of mouth, on the street and even online. Before my Instagram account, there were Facebook pages that were dedicated to long-time residents. Alumni groups from what used to be Johnston High school, which is now Eastside Memorial. These groups tell the story of their school, a building which is still there but has a history that doesn’t get talked about.

RB: That neighborhood has fought so hard to keep that school there, it’s gone through so much…We have been working with the medical school at UT and some high school students at Eastside Memorial on a big community health project, trying to imagine a new version of a community health clinic. We really wanted the high school students to drive and define what that looks like. And the initial prototype turned out to be something that doesn’t look like a health clinic at all: it was part community café, part cultural club. There were doctors there who could do screenings and help navigate the health system, healthy and affordable food made from local recipes from the neighborhoods, and activities that celebrate the culture of the neighborhood. We did a pop-up version of this and now want to get funding to build something more permanent.

AG: That’s really great. I think sharing images online, having a platform that people can add to promotes interactions that just aren’t possible at a downtown museum. And some of these institutions are trying to show some of these materials, I think they deserve some credit for that. Although I always laugh at the suggestion of “come to this side of town to learn about your past.” I think West Austin and downtown for a lot of people is synonymous with a burden; it’s inaccessible, it’s associated with wealthy, downtown establishment, and it’s difficult, even if you are just visiting the public library, to get there, to make time. It’s removed from the community of people who deserve to see it.

RB: It also feels like so much history is still conveyed orally. We have books in school but for most people, the way we learn this history is from each other.

AG: Riding the bus, speaking with coworkers, people want to get it off their chest. They want to talk you. And once you establish where people are from, and once you establish that you grew up here, there is this bond, and memories just flow forth. “I’ve seen so much…” “I remember when this…” “I remember when that…” I had a supervisor at Texas State in San Marcos he was from East Austin. He was a Vietnam vet—drafted in the 60s—and he came back and joined the Chicano Brown Berets movement against the then displacement of families in East Austin. The more I’ve spoken to longtime residents, the more it’s shaped the way I view these neighborhoods. It’s a battleground you know, it’s something sacred that deserves respect. That’s the trickiest and the scariest part for me, is what gets lost. In archeology you dig up a site and record every layer because you know that once we move forward, once the highway is here, once we build this housing development, we will only have the record. And it’s happening so fast, it’s at risk, I don’t understand why now in a time of rampant gentrification, museums aren’t jumping on this. In the great depression, people were recording things, country songs, slave narratives. And here in Austin this is our story, but it’s disappearing everyday.